There's a few things that you've mentioned that would branch off nicely to our subsequent questions. One of that was the collaboration with subRosa on Matrixial Technologies as well as the point about cyberfeminism or any form of feminist knowledge as being a kind of Western inheritance. On the latter, we are also guilty of privileging a specifically Western point of view, even with the references that we are drawing on for the coordinates for this interview. But, yes, there is a need to configure the relationship of exchange between different places in the world as a more active relationship than that of a passive recipient. Different contexts shape the urgent or everyday ways in which we react, respond or live with technology.

In 2003, you were part of Tactical Media Lab, a collaboration between the NUS Cyberarts Programme, LASALLE, and subRosa, a US-based collective of cyberfeminist cultural producers. The project was titled Matrixial Technologies and looked specifically at bioinformatics through art and technology. How did this collaboration started and what were the aims of the project?

It started in 2001 when I moved from LASALLE to the University Scholars Programme at National University of Singapore (NUS) to start the Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative. I started teaching courses there related to lab-based cyberart as well as cyberculture. As part of the initiative, we also had an artist in residence program. We partnered with LASALLE and NUS to invite subRosa to collaborate with us. All the subRosa members came to Singapore and met with us. By us, I mean myself, Margaret Tan, and Adeline Kueh, and our colleagues, students, art and research partners at Lasalle and NUS, who were part of the MatriXial Technologies project.

One of the differences in our collaboration was that subRosa maintained the anonymity of their members at that time and we, in Singapore, decided to collaborate as individuals. We kept it very open, in that each one of us could claim the whole work individually and collectively, as needed, no questions asked. Tan, Kueh, and myself were co-authors on that project. I learned a lot from our conversations. Listening and trust were the key. We developed an interesting kind of distributed way of working together and individually.

At the time, Margaret Tan was developing her very ambitious artwork Virtual Bodies in Reality. This work was also exhibited in Singapore Art Museum as part of the Nokia Cyberarts Singapore exhibition (2001/2002) curated by Gunalan Nadarajan, who was working at LASALLE at that time. Tan’s work then travelled to Taiwan for the above-mentioned exhibition "From My Fingers-Living in the Technological Age: The First International Women’s Art Festival" at the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, curated by Elsa Chen. Tan was Artist-in-Residence and worked with computer science students on this project at the Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative which I was running at NUS. Subsequently, she finished her PhD on Singapore as “smart city” and continues to work at the National University of Singapore.

At that point of time, there was also a growing investment and interest in biotechnologies in Singapore. We could initiate collaborations between subRosa and the scientists based at NUS and Biopolis, where they went to see facilities and discussed stem cell technologies. subRosa members and us. After Singapore, we met again in Amsterdam, Holland, to continue MatriXial Technologies. In Amsterdam, we were part of the Cyberfeminist International Conference in 2002. The third moment of this collaboration was in Chicago at the Chicago Art Institute with Faith Wilding, when we presented as part of the Tactical Media Festival at the Museum of Contemporary Art in 2003.

So much happened in that time, between 1999 and 2005, when I left NUS and moved to the US, to develop this art and technology area, with me and a few others focusing on cyberfeminism. To think that we did all that in 2003 with subRosa, collaborated across the world with a commitment to mutual respect and co-creation. Margaret Tan and I subsequently reflected on this collaboration in our presentation at ISEA2008 in Singapore. This was also before the advent of Facebook, WhatsApp and Youtube which may make connecting easier, so we used a lot of email as you can imagine. We were interested in the different forms that collaborations could take so as to fulfil intersectional feminist aspirations.

Mindspace is a conversation series that charts the conditions of various technology-informed art practices and practitioners in an attempt to present a working history of media art in Singapore.

13 posts

View by

In our second conversation for Mindspace, we are hearing from Dr. Irina Aristarkhova, who is currently a Professor at the University of Michigan where she lectures and writes extensively on contemporary art, theory and digital studies. In 1999-2001, Dr. Aristarkhova was also part of the faculty at LASALLE College of Arts teaching feminist and cyber theory and was responsible for the direction and inception of the earlier Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative in the National University of Singapore.

Samantha Yap and Teow Yue Han of Hothouse speaks to Dr. Aristarkhova about her time in Singapore, cycling through key projects and strands of thoughts throughout the late 1990s and 2000s, and reflecting on her engagement with cyberfeminism, feminism, and early engagements with media art.

Regarding the initiating of this series of conversations, we were reflecting on how this sharp pivot towards digital formats appear to eclipse the consideration of there being a rather vibrant media landscape in Singapore, before the pandemic and particularly during the 2000s. It’s also important to reflect on how many female artists were also at the forefront of this development at that time. Through our questions, we would like to cycle through some key projects and strands of thoughts that you've written about or worked on throughout the late 90s and 2000s so that we can take some time to reflect on what was the media landscape in Singapore like at that time especially when it felt like there was a heightened interest in technology and a wave of technology-informed events and practices. We’re also interested to hear about the engagements with female artists you had, and any key artworks that left an impact on you. To start off, how have you been? How are things over there?

It’s all good. Just busy with the start of a new semester here at the University of Michigan. I’m teaching a new online course called Digital Feminisms, it’ll be fun. So, it’s good to reconnect and learn about what you do at Hothouse because I think that many questions which we raised in earlier years about technology and culture are coming back because of the pandemic and our current digital lives.

A Self of One’s Own, 1999, the publication presented an exhibition essay and artist biographies, statements and images from the exhibition showcasing works by participants of the Feminist Art Workshop conducted by Irina Aristarkhova at LASALLE College of the Arts.

A Self of One’s Own, 1999, the publication presented an exhibition essay and artist biographies, statements and images from the exhibition showcasing works by participants of the Feminist Art Workshop conducted by Irina Aristarkhova at LASALLE College of the Arts.

Moving on to our deep dive into the past, we wanted to start by recalling the Feminist Art Workshop held at LASALLE College of the Arts in 1999 and its resulting exhibition, symposium and catalogue, A Self of One’s Own. Unfortunately, the workshop did not continue past its first iteration, and who knows what the future may hold in terms of reviving it, but can you share more with us? Namely, what were the impetus and the intention of the workshop? What was your biggest takeaway from the workshop?

I offered a hybrid seminar-studio course in the Spring 1999 semester at LASALLE and titled it a “Feminist Art Workshop.” The idea was to read feminist theory together as a collaborative collective of art students who would then go and make work, bring it back to class and get feedback that would be informed by ideas and works of contemporary feminist artists, theorists and art historians. One of the key results of that workshop was that collaboratively, the students, another lecturer at LASALLE, Adeline Kueh, and I decided to do an exhibition. The exhibition and a symposium were called A Self of One’s Own. Adeline and I subsequently raised funding to publish a catalogue.

A couple of years ago, when I visited Singapore, the participants of that event, Adeline Kueh, Margaret Tan, Shirley Soh, and I met again and realized that it was a 20-year anniversary of the Feminist Art Workshop and A Self of One’s Own exhibition.

For our 1999 symposium, we invited a leading feminist artist in Singapore, Amanda Heng, as well Dana Lam from AWARE (Association of Women in Action and Research). The workshop and symposium participants were important to Singapore’s feminist art history. That event was a collective effort.

If you look at the exhibition’s catalogue, with the wonderful cut-out images and the multiple languages on the cover, you would recognise that the feminist, psychoanalytic, post-colonial and contemporary theory that we read as part of the workshop was informed by our differences, by multiple “selves” waiting to be born as part of the feminist practice – our own selves, and not just those identities that our societies wanted from us.

It was not so much about presenting a front like the United Nations, but more about how our notions of self, are still a project, in a feminist sense and a post-colonial sense. They are an existential and political project.

After the workshop’s success, I joined LASALLE to teach other courses in contemporary art theory and history. I taught there until early 2001 when I was invited by George Landow to move to the National University of Singapore to start the Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative with the University Scholars Program.

Throughout my intellectual life and in the development of my books, I have always been interested in and collaborating with contemporary artists because I consider many contemporary artworks as significant as activism for social change. As a scholar, I’m specifically interested in philosophical, political, cultural and social alternatives: if we want to move from where we are now, as a community, to somewhere else, where and how do we move? For me, art and activism prototype and enact social change.

Art is important because of the possibility of building something new. I’m very interested in the moment of creating something new. I believe that creative makers have a lot to contribute to those who seek progressive change in society. That is a larger theoretical premise — that theory has a lot to learn from contemporary art and activism that already imagine alternatives to the status quo and put them into practice. So that we can discuss those alternatives, engage with them here and now, in our lifetime, and not just always imagine good things happening in some distant fuzzy future or in literature and science fiction.

Irina Aristarkhova, Virtual Chora: Welcome, 2001, image courtesy of Irina Aristarkhova.

Irina Aristarkhova, Virtual Chora: Welcome, 2001, image courtesy of Irina Aristarkhova.

So much of feminist work and knowledge comes from actively finding the language to articulate or disarticulate what has been witnessed or experienced. As with so many other fields, education plays a crucial role in initiating conversations and considerations about how our realities are shaped by gender, as well as class, and race. Can you share more about what you taught at LASALLE and what was the reception to these courses like? Were there some key ideas from then that you felt have persisted in informing your work today or that you continue to teach today at the University of Michigan?

I taught quite a few classes at LASALLE. My dissertation was already focusing on technology and notions of subjecthood or the self in relation to machines. I was thinking about Sherry Turkle’s work at that time. One of the courses I taught was focused on cyberfeminism. Another course was on technological embodiment where we thought about cyborgs and artists like Stelarc. There was also a course on Russian Constructivism and going back to the question of the avant-garde with the history of the Bauhaus where technology was a huge part of the project. It was the idea that artists were changing society, working with machines and technology, like printing technology and other industrial machines. I experimented with my curriculum and taught that course solely based on women artists from the Russian avant-garde. I don’t know if anyone else ever taught a course on Russian constructivism and had art history examples only of women artists. Those slides that I was showing are still probably somewhere there in LASALLE’s library.

The movie, The Matrix, came out, as you remember, in 1999 as well. One of our LASALLE collaborators in cyberfeminism was a famous American artist Faith Wilding and the cyberfeminist art collective she founded with several other artists, subRosa. In fact, we did a project — Adeline Kueh, Margaret Tan, myself and subRosa members, called Matrixial Technologies, in the early 2000s.

As a result of those early collaborations and conversations, I became very interested in questions of gender, technology, and space. What is the Matrix? Why Matrix? I came up with a theory of matrix as a welcoming space and even made an artwork called Virtual Chora, which was exhibited at the Singapore Art Museum. In this work, a separate server supported a website to provide 50MB of free space for users, without any passwords. That was before YouTube, as you can imagine. Virtual Chora’s Homepage had an image of smiling lips, Mona Lisa-style, questioning cyberspace as the matrix / empty space imagery of “Chora.”

There is some documentation as part of the Cyberarts Exhibition, curated by Gunalan Nadarajan, over here (the link plays with Flash Player) and my essay about Virtual Chora which was published in "Technics of Cyberfeminism: The Mode is the Message” and translated for the catalogue of the First International Women’s Art Festival in Taiwan “Women, Art and Technology” curated by late Elsa Chen. Chen’s exhibition and symposium took place during the first SARS pandemic, so travel, as I remember, was disrupted between Singapore and Taiwan, in 2003.

When I moved to the US, I continued working on the topic of the welcoming space and technology, and wrote the book on the notion of the matrix as connected to the welcoming space. It is called Hospitality of the Matrix: Philosophy, Biomedicine, and Culture and was published by Columbia University Press in 2012. The beginning of that book can be traced back to that time in Singapore and our collaborations with subRosa. In Singapore, unlike in Europe at the time, technology was not just a utopian or dystopian vision. I could bring my students to experience new technology, such as virtual reality or haptic devices, in NUS in 2002, so it was not just a fantasy. It was important for me to acknowledge that and reflect on our technological experiences in real-time, as well as to enable my students to look at it from artistic and critical humanist perspectives.

At that time, we discussed a lot about what it means to have access to technology. Who has access and who doesn't? This continues to inspire me and I’m still thinking about how our lives are not just affected by technology but also about what kind of creative interventions are possible.

Especially now, when we're talking about this, the way that technology is now enmeshed in our lives is completely different from two decades ago. Enough time has also passed for us to problematise our initial positions of viewing technology as a utopian solution, and to even assess how that has both failed and generated many other projects and movements in its wake.

With this, we want to start talking about cyberfeminism. First, we might have to loosely sketch what is covered in the wide net cast by cyberfeminism. We can attempt that by looking at artist collective VNS Matrix and writer Sadie Plant who both independently started using the term “cyberfeminism” at the same time and in different parts of the world. In some sense, this pluralistic origin story can also hint at the decidedly pluralistic approach that characterises cyberfeminism and its attempts not to be contained by a singular definition. In 1995, Sadie Plant writes of how cyberfeminism “implies that an alliance is developing between women, machinery, and the new technology” and this term “alliance” is interesting in thinking about the relationship between women and/or other minority groups may have with technology. Cyberfeminism was sparked by identifying how technology could offer new and more hospitable ways of being, relating, and resisting. Looking back, there was a shared projection of technology as an emancipatory tool for change that has been fiercely contested in recent times. We realise how the internet and technology can continue to perpetuate bias, violence and inequity, especially insidious as it becomes even more deeply entangled in the rhythms of our lives. It’s been more than two decades since those early conversations around cyberfeminism, how would you relate to cyberfeminism now? Do you feel it’s still something that holds resonance?

Whether it still holds resonance, absolutely yes. I would refer you to the Undercurrents listserv (2002). The project was initiated by Maria Fernandez, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, and myself in 2002 as an attempt to consider what these configurations of new media, art, gender, and technology do within the global context, and especially, through a post-colonial lens. I always felt, together with Maria Fernandez and Coco Fusco, that Western white women's voices have been over-represented, within both feminist and cyberfeminist discourses, and Undercurrents was supposed to be a space for multiple viewpoints without one leading voice.

My attempts have been to not just “internationalise” cyberfeminism but also to present a sense of solidarity, extending from Chandra Mohanty’s notion of feminist solidarity from a comparative perspective. I think it’s so potent and still resonates today. Contemporary cyberfeminism has taken off in a much bigger way than when we first started, with Donna Haraway, VNS Matrix, Sadie Plant, OBN and subRosa cyberfeminist art collectives, and Rosie Braidotti. Braidotti’s text “Cyberfeminism with a Difference” was especially important to me in finding that community, prompting me to contact Alla Mitrofanova and Irina Aktuganova, who were already connected to the international cyberfeminist community and who organized a conference on cyberfeminism in 1998 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and invited me to present in it. My text “Cyber-Jouissance: A Sketch for a Politics of Pleasure” was the result of those early cyberfeminist events, and was subsequently translated into English and German.

Thinking about technology philosophically, critically, as a feminist scholar, that's where I come from. As you also mentioned in our first correspondence, contemporary writing such as Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism, as well as texts by younger generations of cyberfeminists have gained more visibility. I very much think that it's not just surviving as a field, but it's also thriving and expanding.

Also, the fact is cyberfeminism has never claimed to be some one grand theory. Referencing what OBN (Old Boys Network) did when they were mapping out what cyberfeminism was not and their hope to create a space for various people to access and enter it, represented their desire not to perpetuate an exclusive space and stubbornly hoard notions of what cyberfeminism was or could entail. The open access was important to all of us then.

That’s also how subRosa operated and they also came to Singapore to collaborate with us.

However, a lot more has to be done to make intersectional methodology and practice a commonplace in feminism and cyberfeminism. 20 years ago, Western white feminists did not have agendas inclusive of cultural and racial difference as much as, one hopes, we do today, and that was evident in my collaborations with many of them, myself coming from Russia (or Singapore) at the time. Whether it was twenty years ago or today, technologically speaking, Singapore is much more advanced than many of the Western countries but it might not get the same level of acknowledgement for it among the cyberfeminist community. The question of expectations was tied to gender, race, class, in relation to technology and we must still continue to have difficult but crucial conversations to make sure we unpack each other’s conscious and unconscious biases and expectations.

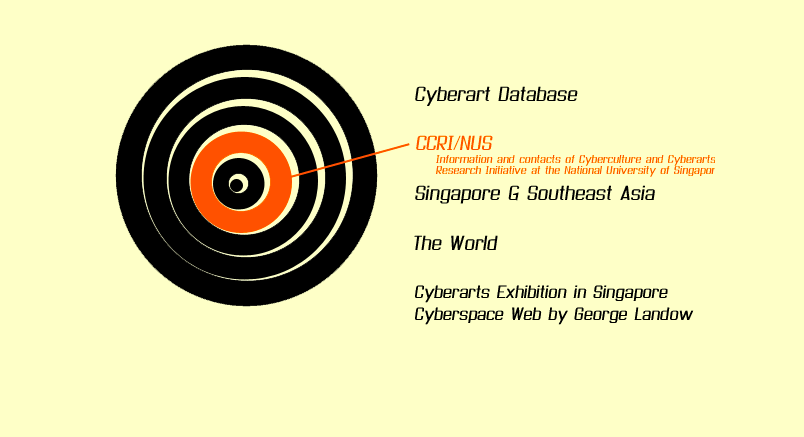

Cyberculture and Cyberarts Research Initiative website landing page. Screenshot retrieved from cyberartsweb.org.

Cyberarts Research Initiative website landing page. Image credit: www.cyberartsweb.org.

You mentioned about the various things happening at that time in the early 2000s, like the interest in biotechnologies, the Nokia Cyberarts exhibition, as well as the Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative in NUS, all of which were part of or shaped the burgeoning media art landscape at that time. The insight to how things were like before may not be so easily gleaned especially with the lack of or difficulty of accessing documentation or a consolidated archive. It’s a wonder to see the Tactical Media Lab website persisting and that’s also how we’ve come to read more about the project.

Could you elaborate more about how you felt like the media landscape was in Singapore at that time, that may have enabled the initiation of projects such as Matrixial Technologies and other technologically-centred works?

There were artists who already worked with technology, such as Matthew Ngui and Amanda Heng. The artists in residence program in NUS was part of the Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative so I could bring NUS researchers in contact with artists. The Dean at that time was George Landow, who wrote Hypertext (1992), the famous textbook on electronic poetry and literature, so he was very supportive and there was a lot of great energy among students and artists too. Charles Lim was also one of the first artists in residence whom I supported at NUS. He was developing one of his earlier works in new media as part of the programme.

As you know, Singapore then had a lot of technology, but it was not so easy to pair that technology with art because that required funding structures and institutional support. For example, NUS did not have an art department and no artists were working at the university. As part of the Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative (CRRI), I had to write the job description to hire artists-in-residence. When I wrote the job description, I made sure to include language that invited artists might not be necessarily trained in painting or other traditional art forms, or even have an art school degree. They might have a background in engineering or creative writing. I included that language so that university administrators would not just carry certain expectations of artists as working only in traditional art forms or media, like painting all day in their studio. They could use stem cell or wifi technologies in labs and engage with other technological and scientific materials. Providing platforms for the new and original trends in humanities and the arts is important, and at that time I considered writing those new job descriptions as important as my own scholarly work on the matrix. Singapore already had a lot of infrastructure and technology to support ground-breaking artworks, such as Margaret Tan’s Virtual Reality art, and I wanted in my own modest way, to help make those connections so that art and technology collaboration would become possible. It was around that time also when the National Arts Council was setting up its funding frameworks.

At the University of Michigan where I’m currently at, different disciplines meet at one art and design school without any silos and departments, that separate us purely by the medium (painting, sculpture, graphic design, etc.). Our faculty and students can work in various media, as well as conduct various forms of creative research with collaborators from other schools, departments and outside the university. So, our students from early on could be proficient in various skills but more importantly, we want them to be leaders of their respective fields and invent new fields and their own forms of expression as they consider them important and needed. One form of art or design does not replace or retire another.

From the University Scholars Programme at NUS, I moved to ICM (Information and Communication Management) programme. When Professor Milagros Rivera became the head of department, it was renamed to Communication and New Media (CNM), in 2003. That’s what I meant by structure. For projects to be supported and enabled, how you name yourself matters because you indicate the scope of work and then we enable certain practices to happen. So that was how that time was, many collaborations and a focus on educating the public and ourselves. Sometimes, within a community, how one relates to or defines media art and technology can vary across different generations. Today, it might not be as prevalent, but back then, we were arguing over words, like whether “cyberart” was the right term to use or was “new media” a better fit. Now, I’m happy that we don’t fret so much over terminology, in 2020, and cyberfeminism is still as young as ever.

One of the funnier moments of that time I recollect was that Singapore Art Museum in 2001-2002 did not have computers to show artworks. And here we are bringing interactive virtual reality artworks which recreated C++ raw data from the Visible Human Project by NUS Engineering students who were really excited to work with the artist. So, we loaned computer screens and servers from NUS. We drove them in the back seat of a car and connected them there at the museum, luckily finding an electric outlet. The museum had no wifi or broadband connection in its galleries as well, and that’s Singapore in 2002! This was before museums became more interactive or receptive to different forms of art. I know it is hard to imagine today that we had to bring computers from NUS to show Margaret Tan’s work. There is now the Art Science Museum.

This project, Virtual Bodies in Reality by Margaret Tan, continues to come up in my own thinking and research, because I think that work was very significant but has not been written about yet as much as it deserves. So, I might come around and write about it soon, or team up with another researcher, because I think you were right, that we were so “go, go, go” all that time then, we didn’t properly take the time to sit, document and archive what we were doing, or understand its historical significance. I am grateful that you found these texts and documentation about “Locating Cyberfeminism in Singapore” (2008) because we were busy then and now it’s great to have this opportunity to reflect on these earlier projects.

I was quite fortunate to be able to encounter these traces, it probably started when I was visiting Koh Nguang How with his archive while it was with NTU CCA Singapore at Gillman Barracks. He had a very extensive collection of art exhibition or project collaterals all the way to the 2000s and earlier. It was there I started also encountering various feminist or female-fronted projects. So many of these projects and coming together of people and interests don’t happen in isolation. They are always responding to each other and it started me on this slow intermittent process of trying to excavate other similar engagements of art and feminist perspectives in Singapore.

What you were mentioning about structures as well, it’s important for museum infrastructures to support the presentation of new media artists or works and to ensure that conversations and efforts towards that goal have not just started but are continuing.

So much has happened in a very short period of time. I just recalled also that Song-Ming Ang, who represented Singapore in the latest Venice Biennale in 2019, was a student in my Cyberarts class in NUS, in a specially designed Cyberarts Lab. Later I was his senior thesis co-advisor because he wanted to write about technology while studying in the English department, and was looking for someone who would be an appropriate thesis supervisor for that theme.

I think that I saw my role as a person who would create space — physical and intellectual — to help make things happen in this area between technology and culture. I don’t believe in giving my students 20 books to read, I would rather they have the space to properly think about one of them, but deeply, and then see connections, dialogue, with another 19 books. One of the first assignments in that Cyberarts class was creating a digital self-portrait. We were trying to think about what self-portraiture encompasses before selfies became selfies today. It was very interesting, because everyone was bringing in different perspectives, including digitising photographs of their grandparents, and we were also thinking about what it means to have a digital self. At the time, not many classes yet considered what it means to live digitally online. Today it is a commonplace, though still, a complex topic, but now we have peer-reviewed research we can offer students created by our colleagues and collaborators. At Michigan, I work at the newly created Digital Studies Institute, that considers such issues.

We had a lot of fun in that space at NUS as part of Cyberarts and Cyberculture Research Initiative. I remember a reporter from The Straits Times who came in when we opened the Cyberarts Studio Lab and she asked about my goals for the Cyberarts class. I told her that I wanted students to be happy in class. The reporter did not want to print that. But I still think that learning something meaningful can make one feel happy. Being happy while learning is a great motivator to work harder, leading to professional success.

For me, it’s a conviction that our best work and best thinking comes when we give ourselves some space to breathe and to get into the special zone. That also requires permission to be ourselves especially with there being so many pressures and societal expectations tied to education or art practice. Technology then would be another layer of something to consider in that regard.

You mentioned a lot about providing space and being able to initiate and facilitate the artist residency programs. The work of facilitation and supporting artistic practices has a lot of resonance with the thinking that you’re doing now, which focuses on hospitality.

Moving back again in time, in 1999, you wrote two papers that engaged with the possibilities that cyberfeminism represented, "Cyber-Joussiance, A Sketch for a Politics of Pleasure" and "Hosting the other: Cyberfeminist strategies for net-communities.” Both writings looked at the viability of cyberspace and cyberfeminist strategies especially at a time where the Internet was making itself popular and available to most people.

We want to draw attention to something you wrote in the second paper — “[I]n following the feminist and deconstructive critical traditions of opening up limits, have to make the closure and exclusivity of net communities a constant point of contestation so as to open doors into and actively create hospitable spaces for ‘others’—whether different in terms of class, ethnicity, religion, culture and sexual orientation.” (from “Hosting the other: Cyberfeminist strategies for net-communities” in Next Cyberfeminist International, 1999)

Can you elaborate more about how and why thinking through hospitality and openness was important to you both in your work with hospitality and cyberfeminism?

Thank you for this question. There’s a couple of things worth highlighting here. First is that I am very interested in how to keep things open. We’re full of differences, right? We might discover that we disagree. Also, we are full of anxieties about what these differences might mean and how they may impact our lives. So, there also needs to be strategies and negotiations about how to approach difference. That’s also why hospitality has been an ongoing interest because I think that the quality and impact of an encounter with another, whether as a person or as a nation or in cyberspace, that’s important to me as a scholar, educator and researcher, how to keep differences alive while also creating a welcoming space.

The second reason is more personal. Moving to Singapore in my late 20s, from the largest country in the world by land mass, with brutal winters, to Singapore, which was very small with a tropical weather, was new to me, and new differently than the UK, where I did my graduate studies. I was both a guest as a foreigner, and a host, in my different roles as an educator but also with regards to my place in Singapore as a Russian white woman. I was welcomed personally and professionally by many Singaporeans and did not take their welcome for granted then or now.

Recently, I gave a talk here in Michigan as part of the Southeast Asian Studies program about my collaborations in Singapore. First, I had to clarify that I am not a specialist or expert in Singapore. I have friends and family in Singapore and a decade-long experience of living and working in Singapore and visiting since 2005. Professionally, I am very interested in what is happening in art and technology in different parts of the world and through a collaborative and comparative perspective. But that’s all very different from calling myself “an expert” in some part of the world.

Our differences reveal us no less than our common identities. I’m interested in how we can collaborate as equals, without pretending that we have the same amount of power. That lack of pretending that we are treated the same is what might enable us to collaborate with more transparency and more effectively. That also continues even today, we see the need for net communities around the world to be open and welcoming especially with all the continuing vitriol that has been disseminated online and with its consequences in our everyday lives.

Art has an important part in all of this. In my latest book, Arrested Welcome: Hospitality in Contemporary Art, I continue to argue that artists provide us with new paths of thinking, and going forward, as far as relations between us and the world are concerned, as in hospitality. Artists incubate ideas and practices of how we can challenge ourselves to move forward.

On the note of collaborations and artists, we also wanted to reflect on your engagements with various Singaporean female artists.

In the 2007 essay, “Happy Endings: Engagements with Women-Artists in Singapore” published in Domain Errors: Cyberfeminist Strategies, you reflected on the practices of female artists in Singapore that you were in contact with such as Adeline Kueh, Margaret Tan, Amanda Heng, and Saraswati Gramich, in relation to the possible cyberfeminist strategies they were channelling or that were resonant with their practices. I’m curious about your choice of title of “Happy Endings” and wondering if you can start off from there to share more about your engagements with artists at that time?

First of all, I had no idea, until recently, of the double meaning of this title! Very unfortunate. This is the price one pays for using the foreign language without being exposed to such double meanings. I wish I could change it and I certainly apologize for using it. I wanted to write about how collaborations worked and could work, from my own limited, of course, and partial perspective, as positive engagements. For me, thinking about cyberfeminist strategies and engagements was a question that extended beyond whether specific artists explicitly used technology. It was more of the idea of how digital, video or cybernetic formats helped us work more distributively. That was the impetus of my understanding of cyberfeminist artistic strategies. I also wanted to make sure that certain works and aesthetic strategies that Kueh, Tan, Heng, and Gramich used would be documented. As you brought up earlier, the paucity of documentation and art historical context that often surrounds women’s art and intellectual projects continues to be a problem. This kind of lateral, more horizontal type of engagement, was important. So, we would discuss in advance what would happen in a collaboration or collective, if one of us went a different route or direction. The coming together was more of an undefined collective, and that was one strategy that we used as collaborators in Singapore.

I also wanted to specify how liberating temporality is. Rather than feeling anxious about any future scenarios where we may disagree or fall out, since collaborators in creative collectives are often worried about how the ending or breakup happens, we talked about these endings right at the beginning and wanted them to be “happy.”

It’s also a cyberfeminist practice because it’s unfixed, temporal and changing in its media. You probably work like this too, in Hothouse. When you are thinking about how long something needs to last, whether collaboration or platform, this consideration of temporality can be useful, and even liberating. This also enabled us to work effectively with each other, people can come in and go, and a lot of it was work propelled by our intellectual and creative interests rather than a job title.

With the project Undercurrents, it was to think and reconcile with the idea of a global cyberfeminist network. On that note of thinking about cyberfeminism from the lens of both local and global contexts, Margaret Tan and you have also had a conversation about the attempt of locating cyberfeminism in Singapore.

The dialogue with Margaret Tan in 2008, specifically reflects on the collaboration between subRosa, who came to Singapore to work with yourself, Adeline Kueh, and Margaret Tan. One of the key points was trying to contextualise cyberfeminist artistic strategies within Singapore but also to foreground a feminist model of solidarity in cyberfeminist practice and theory. This attempt at contextualisation and trying to map out solidarity and affinities is important in also unpacking the assumption that many feminist discourses, including cyberfeminist theory, as a “Western” inheritance which you’ve also addressed earlier.

Rather, we would think that such manners of working with and around technology are multiply embarked across the world instead of subscribing to a hierarchical flow of “centre” and “margins” along a grand methodology. Could you share more with us your thoughts on this?

Your question considers the local and global, in relation to modes of collaboration. It also goes back to the structures that we are already situated within, and the immediate conditions of our lived realities. I am now situated in the US, but my everyday life, whether on Telegram or WhatsApp, is as much elsewhere as in the US. What you are alluding to, if I am not mistaken, to a pressure cooker that contemporary notion of productivity is in societies such as Singapore or the US, where technology is so interwoven into everyday life and has been for so long, with the government pushing it into new directions all the time, to continue being a leader in that area. As a result, digital citizens, due to necessity and not just out of their own choice, end up with a kind of a love-hate relationship with technology. As technophilic as it has been in Singapore, perhaps there has not been a better time to really pause and think about it, right now, in the pandemic, what we want in our everyday life.

My attitude and ideas about theory concerning feminism and technology as coming from the West have evolved too. Let me push back a little against this idea that those who consider themselves to be “non-Western,” have to either react to, reject, or accept and assimilate in some form, “feminism” or “cyberfeminism” because Western (presumed often white) women started it. As your question also pushes back against this idea that there are those who are at the margins and those who are at the centre. It’s a matter of changing our maps, our perspective, of the last few decades of shifting margins, centers, powers, movements. This is what the last 20 years have enabled, that people of varying privilege and connection can take on less hierarchical ways of thinking or working together. The “canon” or any other previous knowledge and history are relevant only to the extent that it helps you in your own spacetime and in your own body to be more empowered today than you’ve been, yesterday. Every good university I know is currently revising its curriculum and challenging what the “canon” is, especially the so-called “Western,” canon in the arts and humanities, to make sure that what we teach is empowering to all our students, and not just those who’ve already been “at the centre.”

Which is to say, I don’t think that feminism is a Western invention. It’s an invention of someone who wants to change things in their immediate environment, including gender structures, but also addressing other forms of oppression happening in society. I disagree about giving anyone ownership of these terms because if you are thinking about Black Lives Matter and the #metoo movement, the two most important social and cyber movements in the US in recent history, they were founded by queer African American artists, young activists and intellectuals. So, the idea that feminism is white or the theories we learn are all Western and white, as Margaret Tan explained, should not stop any of us from using them to our own benefit. It does not mean we must plainly accept this existing knowledge or scholarship, but there is so much more today to engage with, for example, this amazing work of Diana J Nucera (aka Mother Cyborg), a cyberfeminist, DJ and digital activist based in Detroit, USA. There is a lot more to choose from, whether in feminism or cyberfeminism.

Rather than a singular origin point, there are multiple ones happening independently and concurrently, which brings us sort of very nicely back to cyberfeminism and how any attempt to define it always ends up like seeing it for all its tangential possibilities and fruitfulness.

To wrap up our conversation, I wanted to return to the present time and if you can share about what have you been researching on or thinking about lately?

Right now, I’m in the early stages of working on a project called The Digital Underground, with Imani Mkandawire Cooper who is a transdisciplinary artist and researcher, completing her PhD at the University of Michigan in the Department of Comparative Literature and the Digital Studies Institute. We are building a hub of various projects that practice original and critical transformations of artificial intelligence, human-machine relationships, and since they are alternative to the mainstream, prefer to see themselves in the underground realm. I am also giving a lecture on hospitality and architecture at the University of Hong Kong, on April 9, 2021. The lecture will be based on my recent article about the architectural studio Buromoscow. As you can see, I am still theorizing the idea of a welcoming space, online and offline.