Double Happiness (1980), Edward Luyken

Shows a cemetry in Singapore, the cemetry workers and gravediggers.

Film Nominated by Toh Hun Ping

Infographics ID: FLM.001

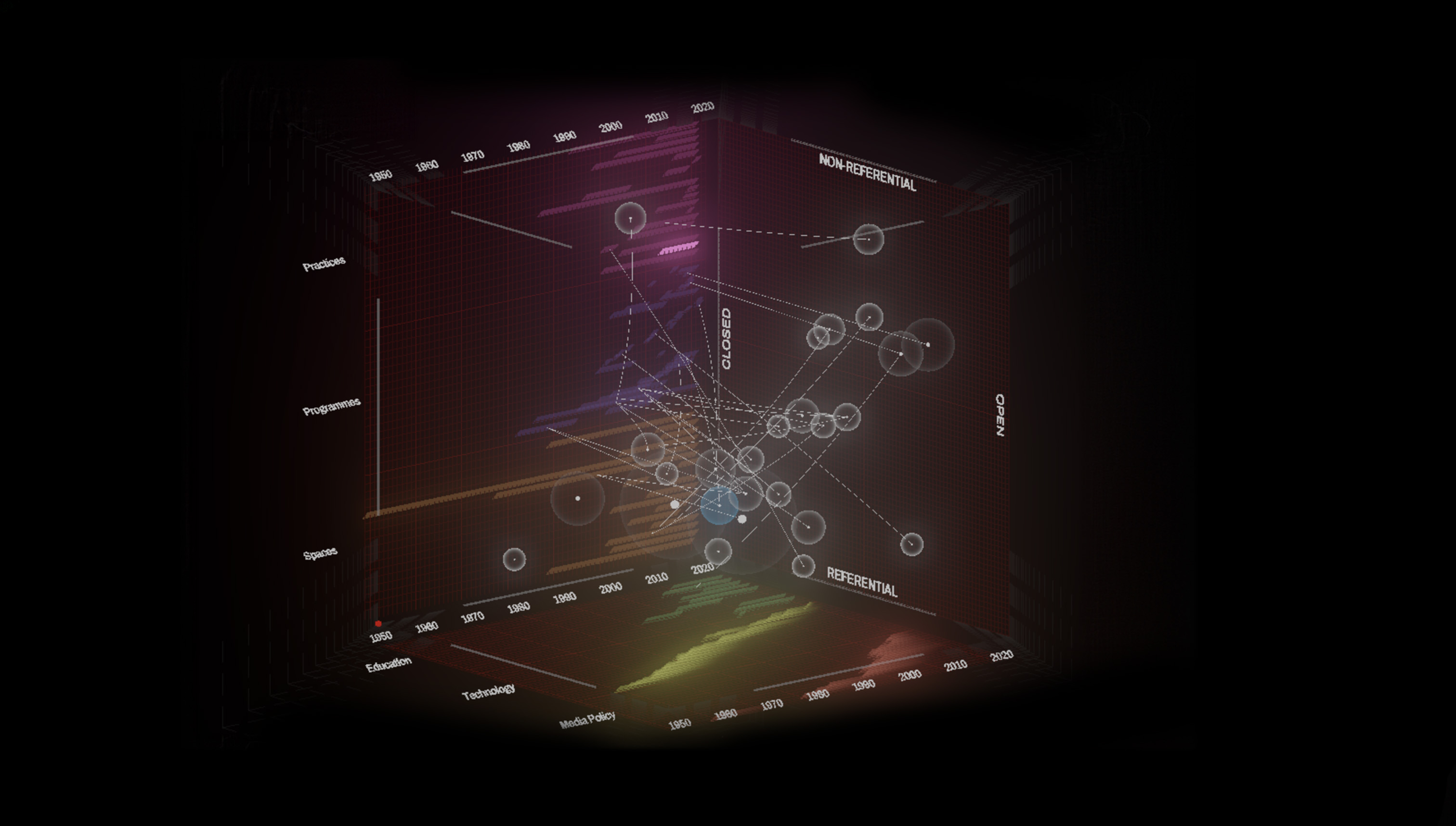

not housed is a transdisciplinary project by Hothouse that maps out the milestones in Singapore’s filmmaking history through exhibitionary and digital interventions. This initiative aims to consolidate, archive, and interconnect various facets of film education, practices, screening venues, and programmes, placing them within the context of evolving media technologies and the national narrative.

not housed aims to spotlight Singapore’s overlooked experimental film scene through an open archive, housing critical artworks that mainstream history neglects. Over the past half-century, self-initiated experimental film practices, though financially challenged, have shone with unique creative vigor. This platform provides a non-imposing space for critical discussions and the expansion of experimental practices that may otherwise fade into historical gaps.

The digital archive connects elements of film education, practitioners, and venues within technological and national contexts. The physical exhibition condenses this timeline, offering a snapshot of key moments in Singapore’s experimental filmmaking. Highlights include an interactive digital archive, a focus on The Substation’s role, historical materials from key spaces, and notably, a film selection curated by practitioners. This offers viewers an opportunity to engage with and watch films that contribute to shaping the definition of experimental cinema.

Toh Hun Ping is a video artist and film researcher. He started the Singapore Film Locations Archive and has been investigating the history of film production in Singapore. He recently began researching anarchistic pursuits in early 20th century Singapore and Malaya and has presented his findings through writing, filmmaking and art installations. In Jan 2020, he exhibited Harbinger, an art installation based on his research at the National Archives of Singapore, as part of the Asian Film Archive’s annual film and art event, State of Motion.

Writing adapted from conversations with the filmmaker

In Singapore, experimental works are often overlooked in institutionalized writings and research. The selected film titles thus reflect a particular interest in titles that have been lost or are not situated.

ECLIPSE (1966) BY CHEONG KOK SENG

Cheong Kok Seng was a filmmaker and writer who was active up till the 80s. Evidence of his filmmaking practice can be found in advertisements of his production company in Sight and Sound magazine. He had made a documentary film called Eclipse (closest possible translation) in 1966, but it is suspected to have been lost. Despite having Kok Seng’s address from 10–15 years ago, Hun Ping never found the courage to approach him to talk about the film. Hun Ping has never seen it, and cannot verify if the aesthetic nature of the work can be categorised as experimental, but this title was particularly interesting as Kok Seng was a Chinese-educated individual who had written about the influence of American avant-garde cinema on him.

DOUBLE HAPPINESS (1980) BY EDWARD LUYKEN

Edward Luyken is a Dutch filmmaker who started out as a sculptor. He is especially reticient about his past works. His film Double Happiness exemplifies attempts of foreign filmmakers to make films in Singapore and the region, as well as the attractiveness of Singapore as a new and exotic landscape to these filmmakers. While it is listed in the Eye Film Museum in the Netherlands and is arguably a work that is “housed”, it is not associated with Singapore filmmaking, and is thus also largely “unhoused” in the Singaporean context. The work warrants some attention due to the fact that an experimental filmmaker had come all the way to Singapore to shoot and complete the work and continues to list it amongst his filmography.

ECHTZEIT (REALTIME) (1983) BY HELLMUTH COSTARD

The German film was deemed a technical success thanks in part to the technological prowess of Singaporean engineer Chan Yuen Chong, who helped design technical development programmes utilised by the production company, and contributed timecode implementations that helped sync audio and video information during the film’s editing. The film reflected Hellmuth Costard’s reputation as an experimental and esoteric filmmaker with “strictly minority appeal”, as well as the successful marriage between art and technology in pushing boundaries of the form — something we often consider as a key characteristic of experimental work. In 1984, the film premiered in Singapore at the Goethe-Institut Auditorium, one of the few institutions that brought in German arthouse and experimental films to Singapore at the time.

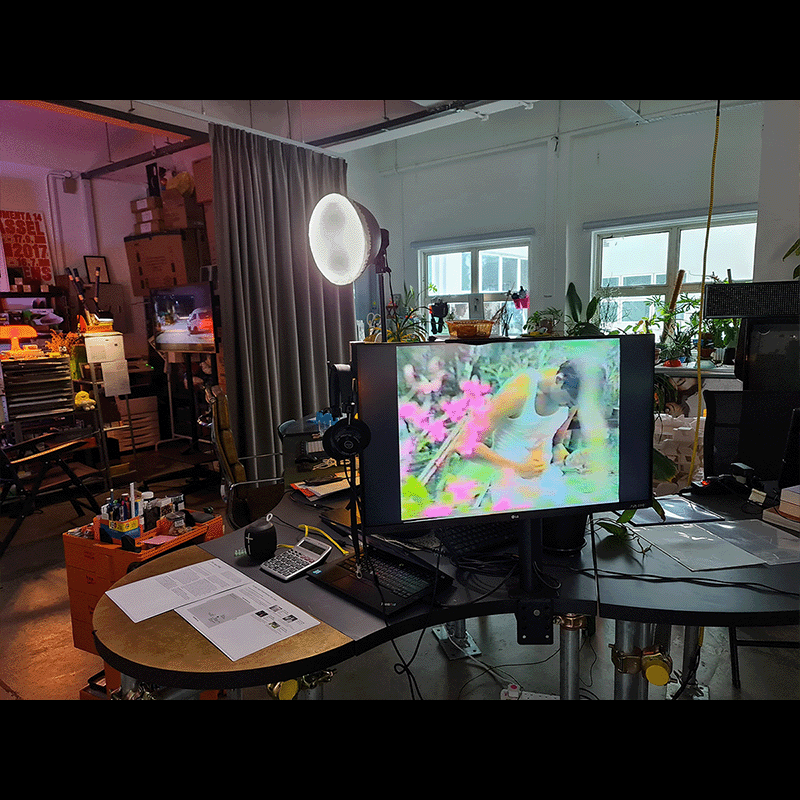

THE GARDEN (1980) BY ONG ANN MENG

A raw piece of work influenced by the screenplays of renowned Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, Ong Ann Meng’s The Garden was a clear attempt at trying to do something different in its time.

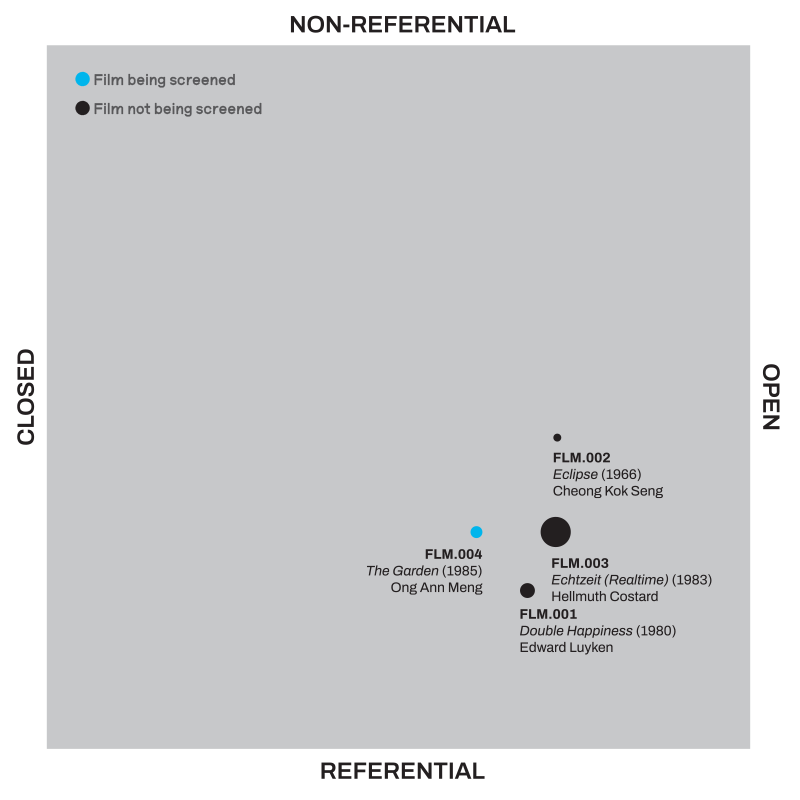

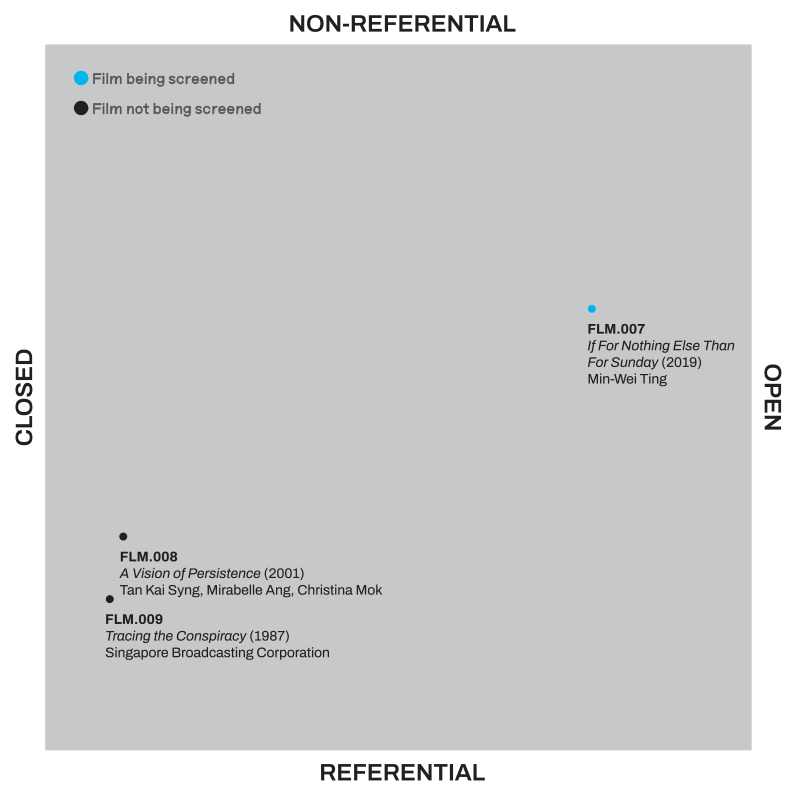

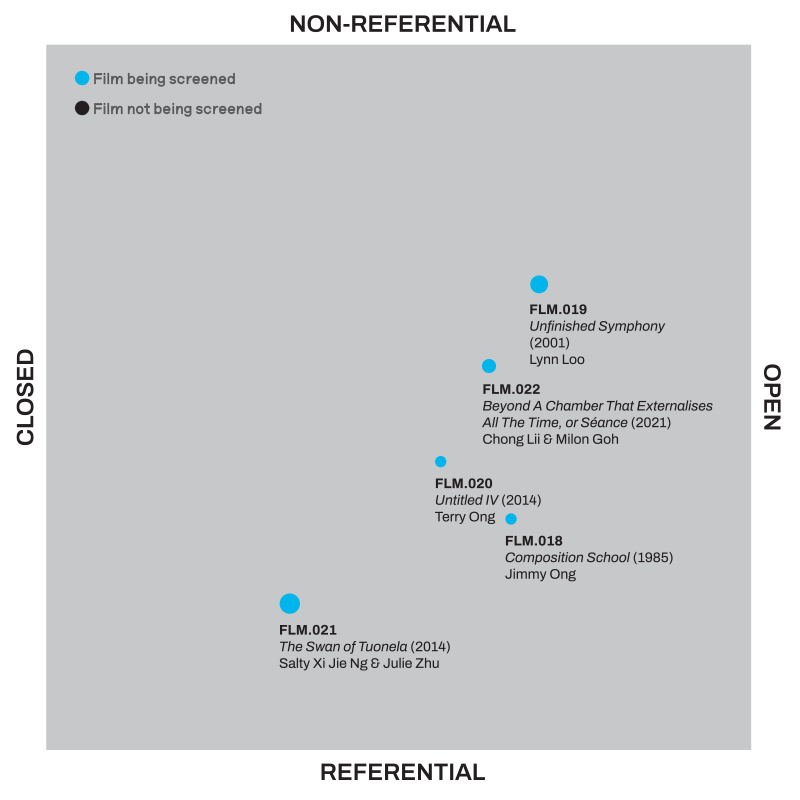

Films were plotted based on two sets of parameters:

Films that are more “Closed” have limited room for interpretation while works that are more “Open” allow for multiplicity of interpretations.

Films that are more “Non-referential” are devoid of representational framework and disengaged from historicised symbols while films that are more “Referential” are more framed by representational elements and engaged with historical symbols.

16mm film, silent, with intertitles. Eclipse (or Corrosion), was Cheong Kok Seng’s first ‘under- ground film’, with clear direction and intent.

Film Nominated by Toh Hun Ping

Infographics ID: FLM.002

Tan Pin Pin 陈彬彬 is a Singapore-based film director and producer. She is known for her works interrogating the idea of Singapore. From traversing Singapore to find out how long it takes to cross the island to traversing the world to speak with her political exiles, her films question gaps in history, memory, and its documentation.

Her films include Singapore GaGa [2005], Invisible City 备忘录 [2007], To Singapore, with Love 星国恋 [2013], IN TIME TO COME [2017]. They have screened theatrically in Singapore and at the Berlinale, Hot Docs, Busan, Visions du Réel and at the Flaherty Seminar. She has had retrospectives at RIDM, Dok Leipzig and Liberation Docfest Dhaka. Tan has won awards from Cinéma du Réel, Dubai International Film Festival and Taiwan International Documentary Festival. She has mentored at DMZ, Busan and Asiadoc. She was a board member of the National Archives of Singapore and Singapore International Film Festival and a founding member of filmcommunitysg, an advocacy group for independent filmmakers. In 2018, she was one of two Singaporeans to be invited to join the Acadamy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, USA.

By Unhoused, I refer to a work that has been orphaned or lost. It could be because the work was censored or where interviewees recorded their interviews under duress or that the work has limited distribution channels so it is not seen.

Probably the most well known film that “disappeared”

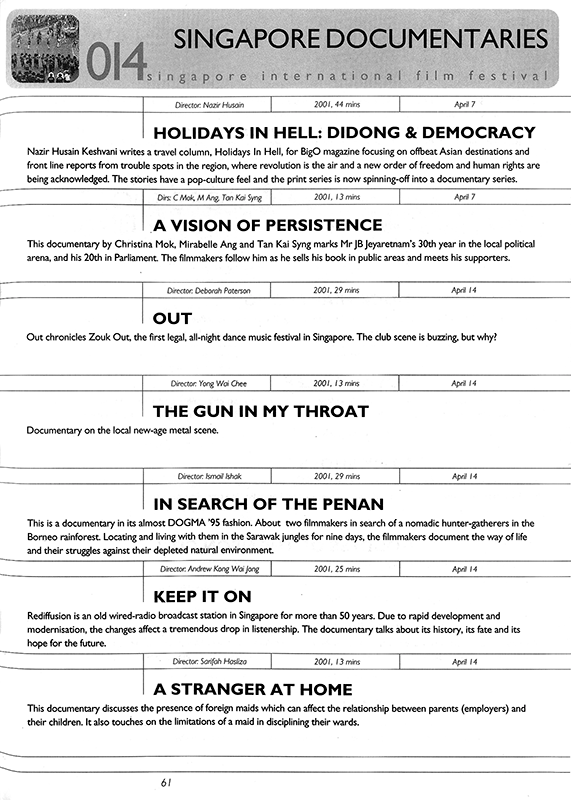

is a 15 minute documentary about J. B. Jeyaretnam (JBJ),

a Singapore key opposition politician, called A VISION OF PERSISTENCE (2001). It was made by Mirabelle Ang, Tan Kai Syng, Christina Mok, film lecturers who made it in a film workshop. They submitted it to screen at SGIFF in 2001.(1)&(2)

A 2002 Straits Times article about this film mentioned that JBJ had ascertained that he was the subject of the documentary and had himself gone to the cinema to watch it at SGIFF, but on the day it was supposed to be screened, it was not shown. The filmmakers did not reply to ST queries. I checked IMDA’s database, it did not exist there either.

I recently checked with one of the film makers. She said that the rushes and copies were given to the police who were investigating them for making the film. The film, by virtue of filming an opposition politician talking about his work may have contravened the Films Act that forbade films that were “party political” in nature.

If Youtube was extant then, the filmmakers could have released it there before the film was submitted to the police, a strategy Martyn See used for Singapore Rebel, a documen- tary about Chee Soon Juan. A copy of A Vision of Persistence and its rushes may still be housed In the police vaults.

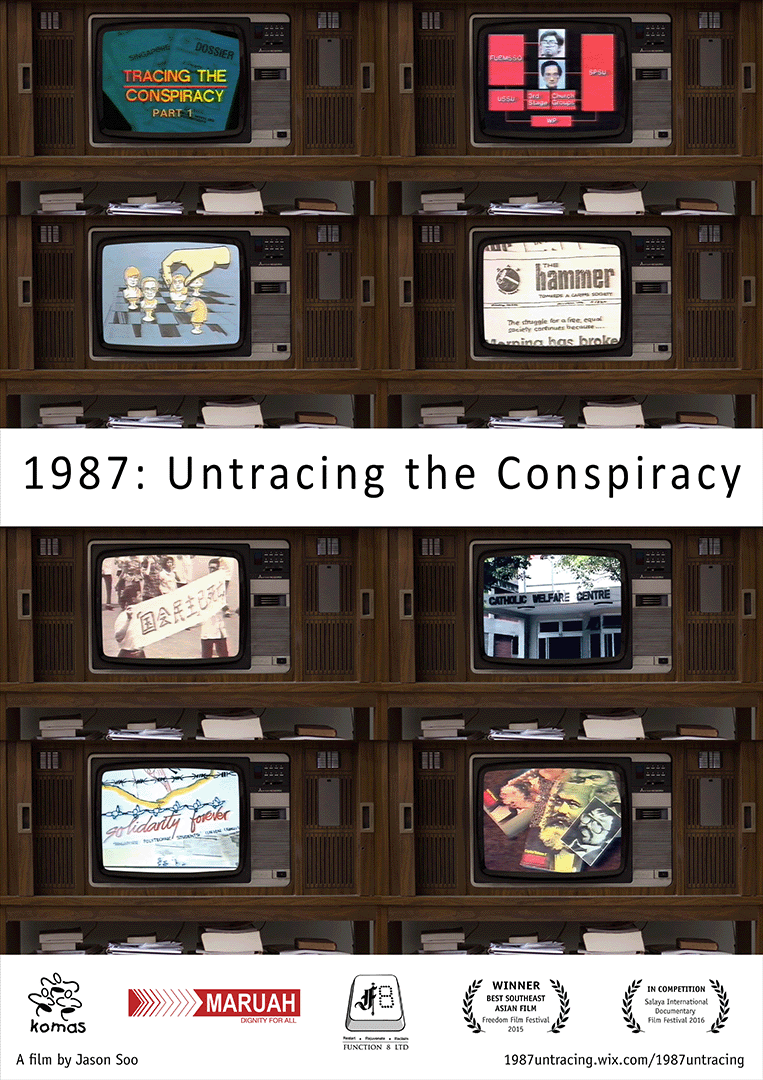

Though available for viewing at the National Library, another work I consider unhoused is TRACING THE CONSPIRACY (1987), a “documentary” produced by Singapore Broadcasting Corporation and shown on TV to explain the arrests of civil society workers in Operation Spectrum to the public.(3) The first time the documentary form had been employed for this purpose.

It features then current affairs presenter Kenneth Liang explaining the network of the conspirators, and later interviewing the activists themselves as they “confessed” in close up, their activities to “undermine” the government. I remember watching it as a teenager, something was not quite right. Recently, watching it again I realised why, it was the script they had to learn. It felt like it was written by the same person. The activists spoke too uniformly about how they were “radicalised” and “infiltrated” by “marxist conspirators” whom the VO insinuated had links with the Malayan Communist Party. There were many awkward pauses, word trip-ups. For example, one of them could not pronounce “radicalise” after several attempts. That this was a fully scripted work was later verified by the interviewees themselves in another documentary called Untracing the Conspiracy (2015) by Jason Soo.(4)

I would like to give space to these awkward pauses, trip ups and tonal shifts, these were the moments the interview- ees revealed themselves that the state TV could not cut out. Vincent Cheng, “the mastermind” in the script, mentioned later in a talk, that he had a different hair parting that day to signal to his friends that it was not him who was speaking, that he was being ventriloquised.

IF FOR NOTHING ELSE THAN FOR SUNDAY(5) is a structural- ist work by artist Ting Min-Wei where he does a first-person walk through of Little India on a Sunday when it is crowded with South Indian migrant workers relaxing there on their day off. He later shoots the same path using the same angles, this time when the streets are deserted, with all life removed. The scenes are intercut so that the contrast between the buzzing streets with the empty streets is foregrounded. With this sleight of hand, the concrete, the tarmac and signage

is heightened. And when the cut is made, the neighborhood tenuously belongs to the workers again, before the concrete silence envelopes the screen again.

As with the Tracing the Conspiracy (1987), it is the gaps and silences that make the work.

(1) Straits Times 4 Jan 2002, Tan Tarn How, JBJ documentary may have broken law.

(2) “Self-Censorship at Singapore’s Film Festival” https://thinkcentre.org/article.php?id=651

(3) https://catalogue.nlb.gov.sg/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/ ENQ/WPAC/BIBENQ?SETLVL=1&BRN=6074164

(4) Untracing the Conspiracy https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eBJqJroWt3E

(5) https://www.mwting.com/albums/if-for-nothing-else-than-for-sunday/

Films were plotted based on two sets of parameters:

Films that are more “Closed” have limited room for interpretation while works that are more “Open” allow for multiplicity of interpretations.

Films that are more “Non-referential” are devoid of representational framework and disengaged from historicised symbols while films that are more “Referential” are more framed by representational elements and engaged with historical symbols.

A sensorial traversal of time and space, If For Nothing Else Than For Sunday is a first-person walk through the Little India district of Singapore punctuated by jumps in time. The camera looks, listens, and moves relentlessly straight ahead, breaking only to cut back and forth in time – taking the viewer into streets and alleyways, quiet and deserted one moment, then in the next, bustling with migrant workers from Bangladesh and India, gathered for relaxation, friendship and freedom on their day off. In so doing, they remake this space, however brief and limited, their own.

Film Nominated by Tan Pin Pin

Infographics ID: FLM.007

A portrait of the former leader of the opposition in Singapore parliament, J.B. Jeyaretnam.

Film Nominated by Tan Pin Pin

Infographics ID: FLM.008

A scripted television documentary showcasing interviews with detainees explaining their arrests in relation to Operation Spectrum.

Film Nominated by Tan Pin Pin

Infographics ID: FLM.009

Sam I-shan is an independent curator focusing on time-based media, photography, and art and politics. She programmes for film festivals, specialising in artist films and video, and Southeast Asian and experimental cinema, working with Singapore International Film Festival, Art SG Film and Videoex Zurich. Exhibitions include Nowhere Here (Singapore International Photography Festival), Sim Chi Yin: One Day We’ll Understand (Rencontres d’Arles, France), Cao Fei and Georgette Chen: At Home in the World (National Gallery Singapore), and Afterimage: Contemporary Photography in Southeast Asia (Singapore Art Museum). She headed moving image initiatives at SAM, specialising in Artist Films, and co-programming the annual Southeast Asian Film Festival. She lives and works in Singapore and Cambodia.

Ho Tzu Nyen’s 4X4 – EPISODES OF SINGAPORE ART (2005) was his response to the inaugural Singapore Art Show organised by NAC, which predated the inaugural Singapore Biennale in 2006. Instead of showing works at SAM or in a gallery,

Tzu Nyen made a television series co-commissioned by and shown on Arts Central. These four films have since become relatively canonised particularly because of their direct intervention in the contextualising and retelling of Singapore art history. However, they can also be historically read in relation to the role of television in the development of video art. For instance, artist, teacher and arts organiser David Hall, one of the co-founders of London Video Arts (now LUX) was commissioned by the Scottish Arts Council to make

TV Interruptions (7 TV Pieces) in 1971 with Anna Ridley and Gerry Schum. These 3-minute films of ordinary actions, unex- pected events or viewpoints were broadcast at random over 10 days and meant to emphasise the chance- and time-based element of video art against the transmission technology of scheduled broadcast television.

The public broadcasting station WGBH in Boston (funded by Rockefeller Foundation under the Artists-in Television pro- gramme) also used television to fund and show video works by artists most notably Nam June Paik, Jud Yalkut, Les Levine and many others, to coincide with video tape recorders entering the consumer market from 1965 onwards. Nam June Paik also worked with WNET in New York, FR3 in France, WDR in Germany (and Centre Pompidou) to broadcast Good Morning Mr Orwell on new year’s day in 1984, the first live satellite transmission of manipulated video art, interactive performance, music and dance that optimistically redeployed globalised mass communication in the name of art.

Read against these precursors, Tzu Nyen’s programmes are a playful, ambiguous take on the medium of television and media in Singapore. From 1999 to 2001 there was a brief flurry of newspapers and television stations being set up

by Mediacorp and SPH, even as cable was just starting to emerge, leading to some jokingly calling it an age of media liberalisation in Singapore. However free-to-air TV was still seen as a fount of centralised information and control. In that light, the somewhat didactic tone of 4x4 (which has also been called dialectical, or Socratic) evokes but also unsettles the still-being-written histories it purports to tell.

Green Zeng and June Chua’s SENTOSA (2007) was a precursor to Green’s The Return (2015), with connections to his photographic series An Exile Revisits the City (2011). It features a film crew following a man who is revisiting a site where he was previously detained. It was shot and edited

in a way to make it look like an incomplete work recovered from somewhere, and had deliberately ambiguous structure, intertitles and credits to make people question whether

it was documentary or fiction. It was screened at the Singapore International Film Festival in 2009 and also at the Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival. The film appears to be based on the story of former member of parliament Chia Thye Poh, who was detained under the Internal Security Act for a total of 32 years, 23 of which he spent in prison, and nine in which he was placed under house arrest in Sentosa. According to Green, it was probably the first time that a film relating to the history of political detainees in Singapore was shown on such a festival platform. When reporters from the local media called him to ask him about the film, he refused to do interviews, and the next time he went on record about the film was in his book Notes for the Future, Green Zeng: A Review 2010–2020.

Liao Jiekai, together with members of 13 Little Pictures, worked with 16mm film in his films and installations, particularly from 2011–2016. SOMETHING FROM THE OCEAN AND SOMETHING FROM THE HILLS (2014) was created and exhibited during Jiekai’s 2014 residency in Aomori in northern Japan and is a project that melds elements of duration, time, space, landscape and the seasons together through the medium of film. It is sensitive to the formal and variable qualities of light, celluloid, projection and diurnal cycles, and is also a kind of one-off performance that will not be replicated, and can only be seen through documentation.

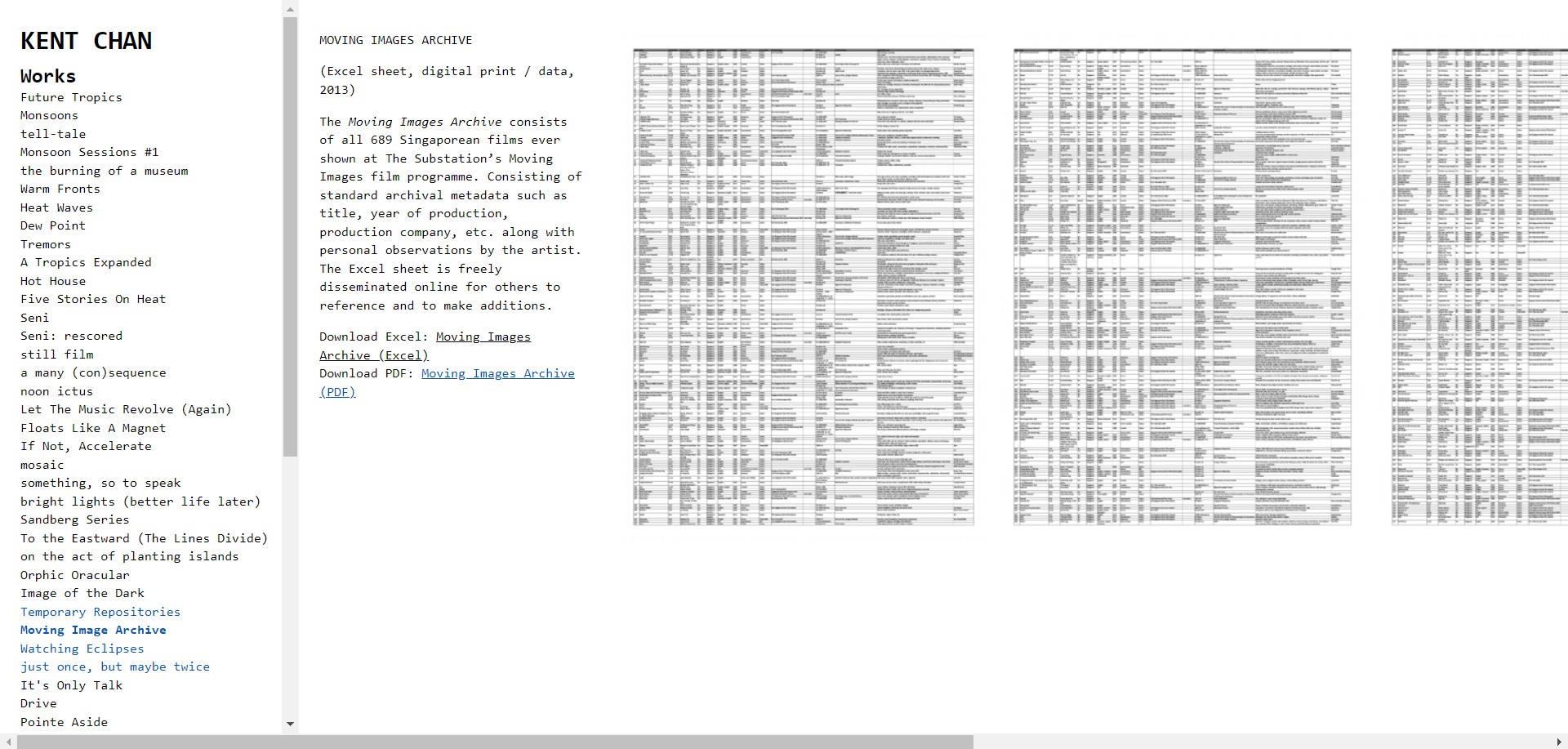

Kent Chan’s MOVING IMAGE ARCHIVE (2013) is a project

that emerged from his early interest in the history and devel- opment of experimental images in Singapore and the region. It is a list of almost 700 films from or of Singapore that were shown at the Substation, and is hosted as an excel sheet

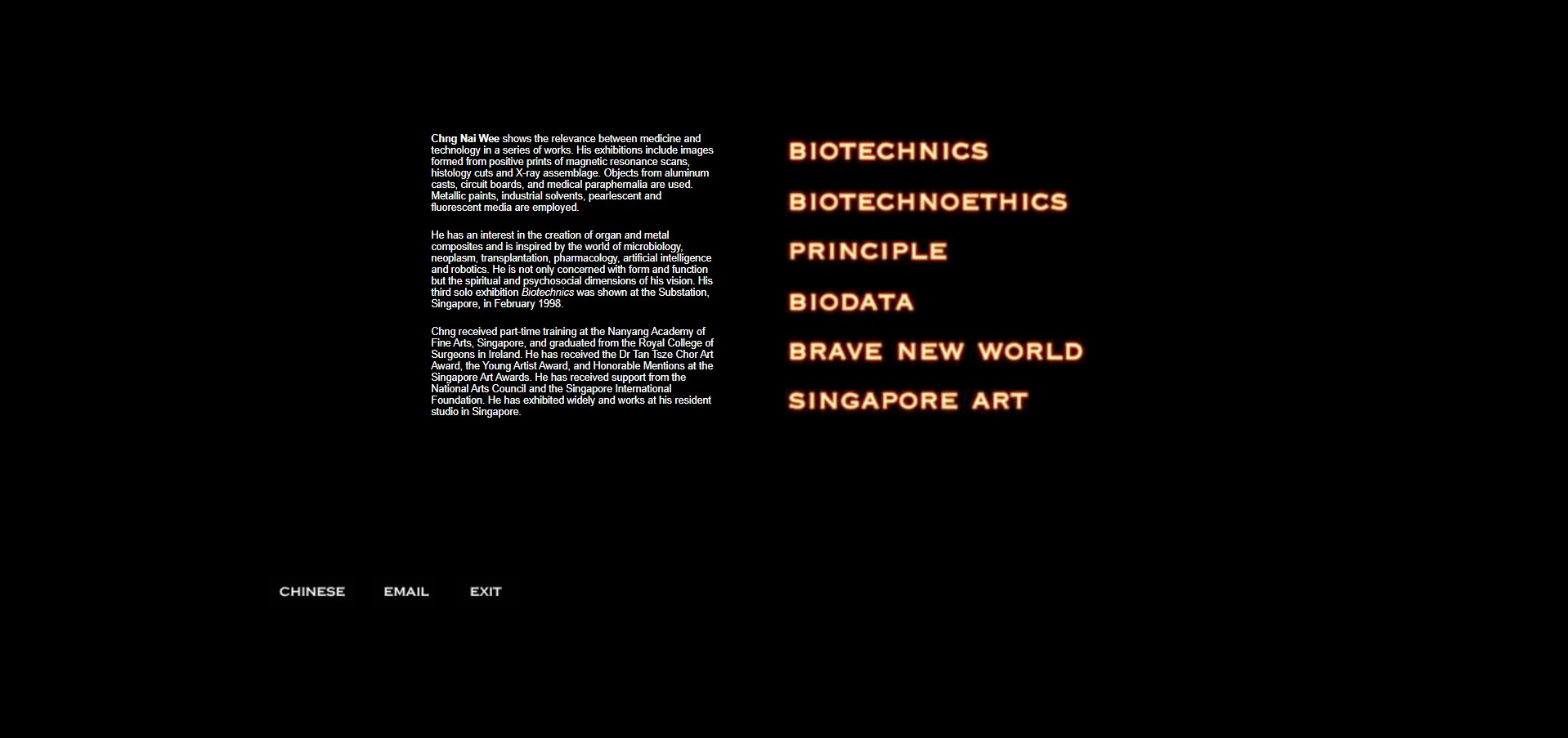

on the artist’s website with an invitation to participate in adding to and distributing this information. Chng Nai Wee’s SINGAPORE ART website lists artists, curators, institutions, events and art-related information dating approximately from the 1990s to 2005. Some descriptions of early moving image works can be found in the “Artists” page in particular.

Both these repositories are a historical snapshot

of a particular period in time in Singapore’s art and film history. Unlike other art forms like paintings, photography and sculpture, access to moving image materials is not

so straightforward, and is often described in text or seen through selected film stills. In the East Asia region one can reference Taiwan’s Theater Quarterly of the 1960s, which described films and theatre productions (including Francois Truffuat, Alain Resnais, Ingmar Bergman, Bertolt Brecht. Richard Chen, Kang-Chien Chu, and others) that were not accessible in Taiwan becuase of martial law. The magazine influenced many artists including Chang Chao-Tang. Tangwai (outside-the-party) magazines (mid 1970s to 1980s) also influ- enced photographers and artists like the video collective Green Team. Even in this day and age, such repositories remain one of the key ways that information about videos and films are disseminated. With the rapid obsolescence of recording and playback technology, such descriptions may well be the most enduring way that future generations can access fragmentary knowledge about moving image works.

Films were plotted based on two sets of parameters:

Films that are more “Closed” have limited room for interpretation while works that are more “Open” allow for multiplicity of interpretations.

Films that are more “Non-referential” are devoid of representational framework and disengaged from historicised symbols while films that are more “Referential” are more framed by representational elements and engaged with historical symbols.

A political detainee revisits the small island where he was exiled.

Film Nominated by Sam I-shan

Infographics ID: FLM.011

A publicly-accessible archive of The Substation’s Moving Images film programme, which began in 1997 and played a significant role in the development of Singaporean filmmaking. It includes 689 Singaporean films shown under the programme’s banner up till 2012.

Film Nominated by Sam I-shan

Infographics ID: FLM.027

A website of artist Chng Nai Wee that consitutes his own visual artworks as well as an archive of artists, curators, institutions, events and art-related informa- tion dating approximately from the 1990s to 2005 under the “Singapore Art” page link. Descriptions of early moving image works can be found in the “Artists” page in particular.

Film Nominated by Sam I-shan

Infographics ID: FLM.028

Fran Borgia is a filmmaker, founder and producer of Akanga Film Asia, an independent production company that aims to create a cultural link between Asia and the rest of the world. He was born in Spain and has been based in Singapore since 2004.

Fran Borgia’s credits include Lav Diaz’s A LULLABY TO THE SORROWFUL MYSTERY (Berlinale 2016 – Silver Bear Winner), K. Rajagopal’s A YELLOW BIRD (Cannes Critics’ Week 2016), Boo Junfeng’s APPRENTICE (Cannes Un Certain Regard 2016), Yeo Siew Hua’s A LAND IMAGINED (Locarno 2018 – Golden Leopard Winner), Kamila Andini’s YUNI (Toronto 2021 – Platform Prize Winner), Jow Zhi Wei’s TOMORROW IS A LONG TIME (Berlinale Generation 2023), Amanda Nell Eu’s TIGER STRIPES (Cannes Critics’ Week 2023 – Grand Prize Winner), and Chia Chee Sum’s OASIS OF NOW (Busan New Currents 2023).

As a filmmaker and cinephile, I experience films differently from other viewers, with my own reading of what they are: what story they are telling me (if any), and how they are visually engaging me; and what remains — mostly in my head, but at times in my heart — is what creates the connection between the film that I have just experienced and myself.

These four films I have selected created a profound dialogue within me when I discovered them. They surprised me and they questioned me. These films are very different too, they are all executed in very personal and unique ways, but all four of them have remain in me since I first discovered them.

They are experimental films, as every film is experimental. The experiment is not limited to the narrative or the visual, but also to the financing and the distribution, how these films were able to be made (and why), and how they have been first presented to an audience (and why).

This selection is personal. When I was given this opportunity, these were the films I wanted to bring to this dialogue on experimental films in Singapore.

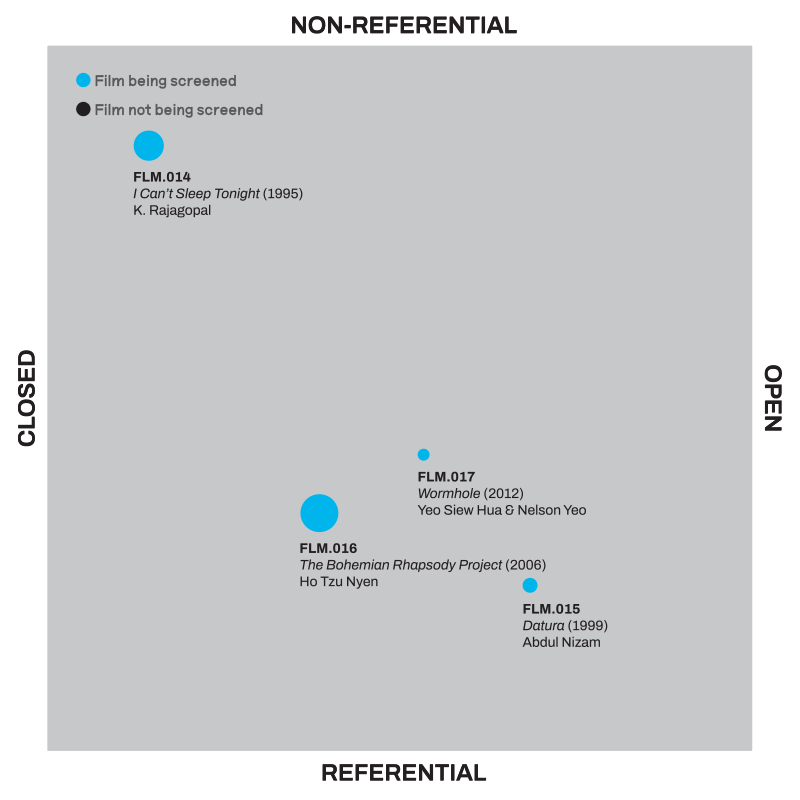

Films were plotted based on two sets of parameters:

Films that are more “Closed” have limited room for interpretation while works that are more “Open” allow for multiplicity of interpretations.

Films that are more “Non-referential” are devoid of representational framework and disengaged from historicised symbols while films that are more “Referential” are more framed by representational elements and engaged with historical symbols.

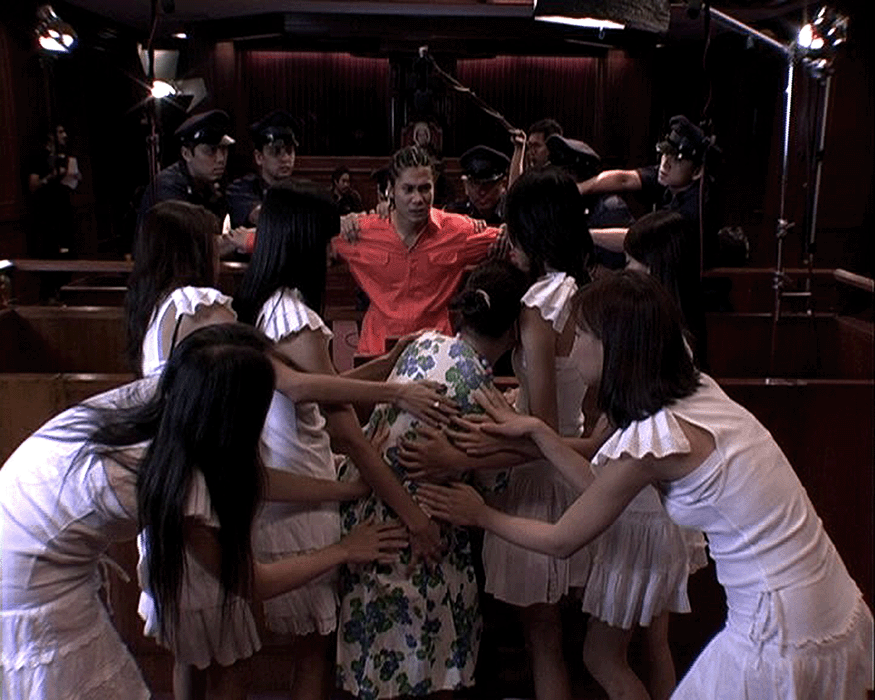

With a script based entirely on the lyrics of the song Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen, and set entirely in the Singapore Supreme Courtroom. A boy is on trial, and his heart is broken at the sight of his crying ‘mama’.

Film Nominated by Fran Borgia

Infographics ID: FLM.016

Thong Kay Wee is a cultural worker and moving image curator based in Singapore. He is currently the Programme Director at the Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF), where he is responsible for the festival’s overall programming strategy.

He was previously the Programmes and Outreach Officer at the Asian Film Archive (AFA) from 2014 to 2021. Aside from overseeing partnerships and promotions, he was responsible for establishing the AFA’s regular film programmes at its new dedicated cinematheque since 2019, with a focus on both contemporary and classic Asian film selections. He has presided specialised programmes such as the multidisciplinary arts exhi- bition series State of Motion (2016–2021) and the film programme Singular Screens (2018–2021) presented as part of the Singapore International Festival of the Arts.

When approaching the notion of “not housed”, I was imme- diately drawn to moving image practices or works that have not always been acknowledged within the “canon”

of Singapore film and art history. A few of them belong to artists who are rooted in other practices, be it installation or performance, and film being just one of the materials engaged within their artistic trajectories. Some of them are more recent works since the 2010s, belonging to a newer generation of artist-filmmakers who have shown promise

in developing a larger body of work. Others are early works by established artists that may help to demonstrate a wider scope in this making of a historical timeline. All of them have left an impression in my years of encountering moving image works from Singapore and I believe they deserve

to be discussed again. My selection is also motivated by efforts to tease out or speculate some connections across what is still a very tenuous “experimental filmmaking” lineage in Singapore, hence every selection may allude to potential relationships or intersections with a few identified “milestones” that can better inform this research exercise.

COMPOSITION SCHOOL (1985) BY JIMMY ONG

The performance art documentation was a one-off perfor- mance staged with Jimmy Ong and his friends from the “One Saturday A Month Activity” (OSAMA) group in 1984. It was a collective that started at the Goethe Institut on Penang Street, where youths could take German lessons, access their library housing theatre magazines from Europe, and watch movies in its auditorium organised by the Singapore Film Society. Toh Hai Leong was a regular feature at these screenings introducing each film at length, with a line-up that included narrative features, documentaries, video-art, experimental and animated films. This was a time when there were few screenings of non-mainstream films in the city and Goethe-Institut, founded in Singapore in 1978, was one of the rare cultural bodies that provided an outlet for the local audi- ence. The organisation was also generous in supporting young Singaporean artists such as Jimmy Ong and K Rajagopal at that time, allowing them to use their facilities like the audito- rium to make videos and test out “performance art” glimpsed from magazines from their library. Lim Geok Puay, one of Jimmy’s friends from OSAMA, coaxed him to document the production and helped shoot the work. It was then submitted and screened at the Singapore Video Competition (1983-1988) in 1985, organised by Singapore Cine & Video Club and the People’s Association. Jimmy Ong used Composition School for an art college admission in US and won a full scholarship in 1984, hence beginning an illustrous artistic practice that has since spanned almost 40 years. According to the artist, this could be the only copy and the highest resolution available of Composition School. Loo Zihan, a fellow Singaporean artist, transferred it from VHS tapes collected by Ray Langenbach, a former Singapore-based artist and educator. A 6 minutes version of the video was screened at the 10th Singapore Short Cuts (2013) organised by National Museum Cinematheque, presented under the retrospective programme Shorts from the Singapore Video Competition (1985–1988) alongside short films like Ong Ann Meng’s The Garden (1985). In one of the sequences, a female student was reciting “Archimedes Principle” in a loop, accompanied by a male student repeating “Comprehension” and Jimmy Ong himself pronouncing “Wang-Li” or pineapple in Mandarin like a broken record. Jimmy had instructed his collaborator Geok Puay to mute the Chinese oracle in the beginning and end of the video.

UNFINISHED SYMPHONY (2001) BY LYNN LOO

Lynn Loo taught music in Singapore before making her first 16mm film in 1997. She studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which includes alumnis like artist-filmmakers Loo Zihan, Liao Jiekai and Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Thailand), and made film works that explore rhythmic and poetic narration using images and sounds as separate entities. Her engagement with film projection performances began in 2004 as a way of thinking about film as fine art, inspired by the 1970s films made from makers involved in the London Filmmakers’ Co-op. She explores the physical qualities of analogue film in all aspects of its production, including its presentation as live performance. The work involves a breaking, and re-thinking, of film time and film space. She has produced gallery installations with the same kind of approach. Since 2005, she has been collabo- rating with Guy Sherwin in numerous film performances and projects. Currently a resident of the United Kingdom, Lynn also serves as a film conservation specialist for the British Film Institute (BFI).

One of Lynn Loo’s first films, Unfinished Symphony

was filmed when she was between locations. Images were collected freely using a 16mm Bolex camera and a Nizo super-8 camera. Without dialogue, images and sounds come together with the intention of making a personal essay. Jonathan Rosenbaum from the Chicago Reader Film Critic wrote a review reflecting that the work “offers fleeting but eerily vivid impressions of her childhood in Singapore, emphasizing the abstract patterns created by the sights and sounds.”

UNTITLED IV (I DREAMT ABOUT YOU LAST NIGHT I SHOULDN’T HAVE YOU’RE NOT THE SAME YOU’RE NOT EVEN HIM YOU’RE SOMEONE ELSE) (2014) BY TERRY ONG

An exploration of subjectivity and objectivity of the moving image/cinematograph, “the filmmaker is a mere conduit; a static flaneur opening himself to the moving exterior” (Low Zu Boon, former film programmer at National Museum of Singapore) where both the images and sound are running after each other, as if each was being reflected in the other, around a point of indiscernibility. According to the filmmaker, Untitled IV resembles a canvas of purely “mental experiences” which themselves reflect or mirror things by natural resemblance based on philosopher Jacques Derrida’s ecriture which described the general condition intelligibility in language as a structure of difference.

Untitled IV also took shape in another form as the Untitled Apichatpong Project (After Apichatpong; For Today, For Tomorrow, Since Then) at the 26th Singapore International Film Festival in 2015, where it was exhibited as a video and light installation at The Substation. It is the other manifestation of a project worked on in Khon Kaen, Thailand, in 2014, featuring the memories and narration of artist-filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

Developing a same vein of interest with exploring mate- rial time in film, Terry Ong made his first video work during a Digital Filmmaking course at Objectifs in 2012 and graduated from a Masters Fine Arts program in Lasalle. He has since completed 6 experimental moving image works.

THE SWAN OF TUONELA (2014) BY SALTY XI JIE NG & JULIE ZHU

Inspired by the Finnish landscape and drawing upon the Finnish Kalevala myth of the birth of the moon as well as Pierrot’s timeless role, the stop-motion animation is set to Sibelius’s mystical classical piece of the same title. This is one of the few film works, alongside a feature documentary titled Singapore Minstrel which premiered at the 26th Singapore International Film Festival, conceived by transdisciplinary artist Salty Xi Jie Ng. She is also known to develop works across cultures and contexts that dances across forms like durational site-specific project, brief one-on-one encounter, co-created meals, performances, conversations, publications, and community space. The Swan of Tuonela is made during her residency at Arteles Creative Center, Finland and performed by Xi Jie herself, who developed a series of performative works channeling Pierrot in a contemporary incarnation. A cosmic scholar, her practice is currently concerned with ancestry, interdi- mensional/interbeing relationing, eroticism, death, and ageing, while examining artistic labour and what gets to be called art.

The film is a nominee for the Best Experimental category at the 6th Singapore Short Film Awards (2015) and won Best Experimental at the CUNY Asian American Film Festival in 2015. The Singapore Short Film Awards, organised by The Substation from 2010-2015, was perhaps the only Singaporean cultural event in recent history to give out an award explicitly for local experimental films.

BEYOND A CHAMBER THAT EXTERNALISES ALL THE TIME, OR SÉANCE (2021) BY CHONG LII & MILON GOH

A graduate from the School of the Arts Singapore (SOTA), Visual Arts department and the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Moving Image department, Chong Lii represents a newer generation of moving image practice emerging from the late 2010s. Beyond A Chamber is a breakout work confronting “Singapore’s protective yet fragmented environment” with a sense of millenial fatalism that teeters across a fraught, dissonant reality. Chong Lii’s practice aims to explore the possibility of merging or levelling disparate spaces, objects, people, and images. Permeable frames of history and ontol- ogy are set against the spectacle of fiction, re-articulating the tensions from which these elements arise. Operating alongside strategies of entanglement and the abject, Chong’s installations and films simultaneously counter and revel within the apparatus of the moving image.

The earlier version of the film was first screened at Singapore Shorts ’19, organised by the Asian Film Archive, and exhibited at programmes by Hothouse and DECK.

Films were plotted based on two sets of parameters:

Films that are more “Closed” have limited room for interpretation while works that are more “Open” allow for multiplicity of interpretations.

Films that are more “Non-referential” are devoid of representational framework and disengaged from historicised symbols while films that are more “Referential” are more framed by representational elements and engaged with historical symbols.

As with the free-association of dream logic, Terry’s images of everyday turned libidinal serves as an active canvas that flows together with the narration. Both are affected by a strong sense of premonition and an acceptance that even that which is most per- sonal to us is triggered by events beyond individual agency.

Film Nominated by Thong Kay Wee

Infographics ID: FLM.020

Ho Rui An is an artist and writer working in the intersections of contemporary art, cinema, performance and theory. Across the mediums of lecture, essay and film, his research examines systems of governance in a global age. He has presented projects at the Bangkok Art Biennale; Asian Art Biennial; Gwangju Biennale; Jakarta Biennale; Sharjah Biennial; Kochi-Muziris Biennale; Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin; Kunsthalle Wien; Singapore Art Museum; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven; and Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, Japan. In 2019, he was awarded the International Film Critics’ (FIPRESCI) Prize at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, Germany. In 2018, he was a fellow of the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program.

Below, this post you will see the films that the contributor have selected for the archive. Each contributor negotiates their own artistic concerns and experiences to approach the concept of not housed and draw connections with the strands of the archive.

In coming up with this selection, I found myself grappling with the semantic quagmire unearthed by the terms that define the scope of the archive: “homeless ”, “engaging with Singapore” and, of course, “experimental”.

What does it mean for a film to be “homeless”? A hard disk sitting in the cabinet of someone’s bedroom arguably constitutes enough of a home for the digital copies stored inside. Inversely, there are numerous films securely housed within state-run archives that have not been seen for decades or that are even completely unknown, perhaps with the exception of the one who catalogued the film, which begets the philosophical conundrum on whether something can be said to exist if nobody knows about it. Indeed, strictly speaking, a truly homeless film is one that is either lost or that no one knows exist, for which an archive cannot be built. For this reason, my own strategy is to define a film’s “homelessness” in relative terms, ie. in relation to a particu- lar tradition of filmmaking from which the film is excluded.

As for the “engaging with Singapore” requirement, I’ve adopted the broadest possible definition by including films that are not only made in Singapore or explicitly represent some aspect of Singapore, but also films made by anyone who has lived in and made work in Singapore for an extended period of time, and for whom “Singapore” therefore serves as a frame through which they, consciously or not, engage with the world.

Finally, my approach to the “experimental” places a focus on films that, intentionally or otherwise, invites reflec- tion on its material conditions of production, whether is it in terms of the materiality of the technological apparatus itself or the broader socioeconomic infrastructures that support the production of the film or, as is very often the case, both.

I’ve also made my selection based not only on the film’s individual merits but also on how each of them can be said to represent a particular genre of filmmaking that I would like to introduce within an expanded genealogy of experimental filmmaking in and from Singapore.

The first film comes from a distinctly non-experimental tradition of state-produced television programming — not least of the genre of “televised confession” deployed as a media weapon within the state’s security apparatus — but to the extent that it documents a moment of precarious mediation in the early days of colour television in Singapore, it demands consideration for its incidentally experimental aesthetics. The inclusion of this film also contests any restriction of the archive to films that have yet to be housed in an institution insofar as it is a film for which no publicly accessible copy is available despite a copy (most likely) being stored in the holdings of the television station.

Likewise, the second film resides in the collection of Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong but sits outside of the genealogy of experimental filmmaking as a video residing in a collection of performance art documentation in Southeast Asia by the for- merly Singapore-based artist and educator Ray Langenbach. In fact, as a record of the 1992 Black May uprising that took place in Bangkok in resistance of the military coup the year before, the film neither qualifies as a documentation of performance art in the technical sense. However, the similar- ity between the techniques used in filming street protests and those used in documenting performance art, as made apparent by the videos in the collection and Langenbach’s own observation, calls upon us to consider performance art/protest documentation in their own aesthetic terms.

The final two films in my selection takes the engagement of Singapore “from a distance” as the basis for developing an experimental approach to filmmaking. One is a video made in 2008 by the London-based Singaporean artist Erika Tan using footage shot during a 2004 residency in Shanghai that can be read as a reflection on her own condition as a (doubly) dias- poric Chinese Singaporean. The other was completed by the Japanese duo SHIMURAbros during their 2017 residency at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art in Singapore. Produced in the tradition of structuralist cinema, the film, comprised of a single shot pointed from the artists’ residency space towards the nearby ports and oil refineries on a stormy night, reflects as much on the structure of film as on the infrastructure of the city-state itself.

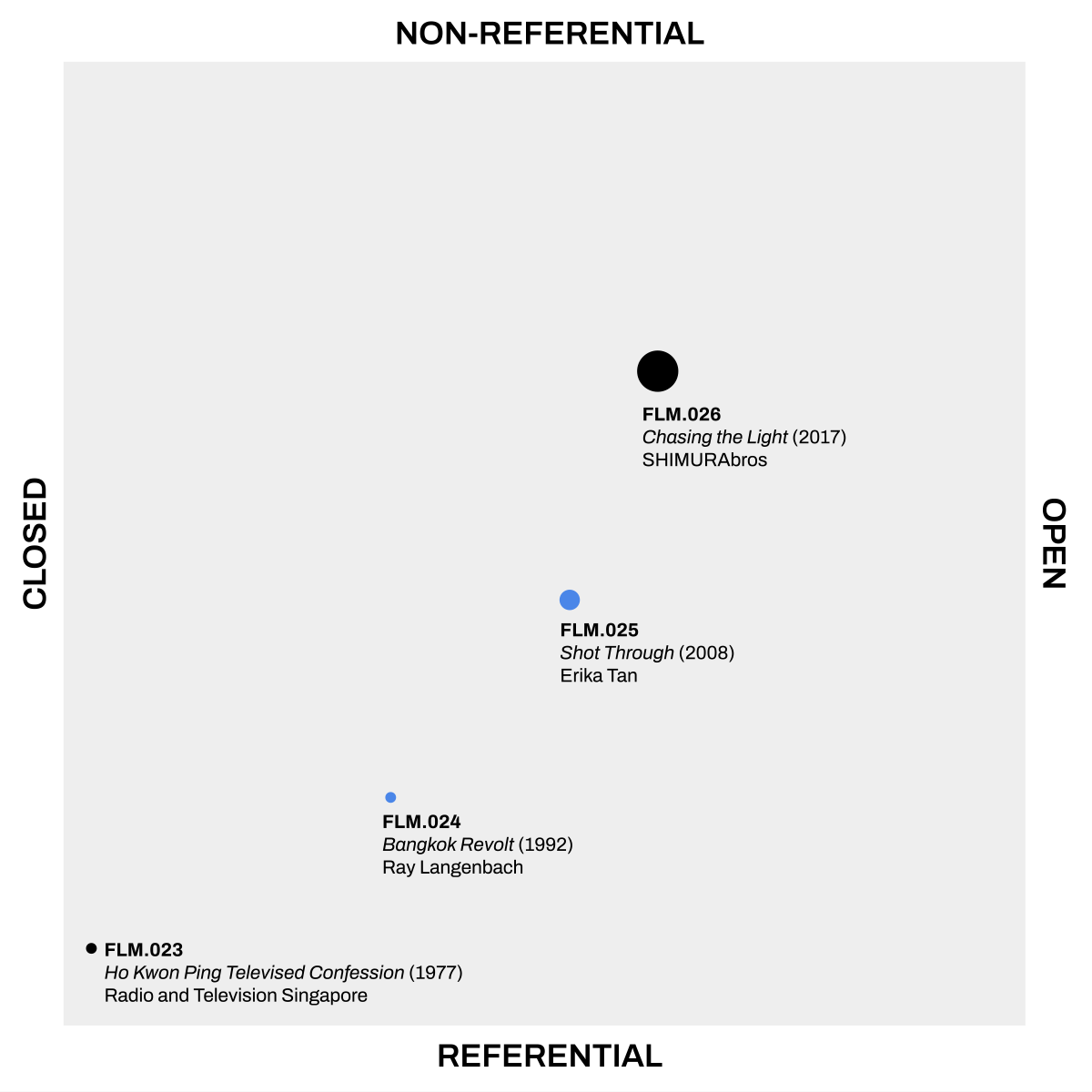

Films were plotted based on two sets of parameters: Films that are more “Closed” have limited room for interpretation while works that are more “Open” allow for multiplicity of interpretations. Films that are more “Non-referential” are devoid of representational framework and disengaged from historicised symbols while films that are more “Referential” are more framed by representational elements and engaged with historical symbols.