Fragment I: of Beginnings, Endings, and Continuities (part 2)

It is important to note that within Hothouse, its members are no strangers to the processes of collectivising, particularly within the local arts context. Urich, for example, has also been part of formative groups such as The Artists Village and the Printmaking Society of Singapore. Yue Han, in particular, articulates a nostalgia and yearning for the kind of relational, community-driven spaces that are now rare in Singapore. In our conversation, he gestured to Post-Museum’s physical space as a site where “anybody can just come and hang out,” a porous, lived social architecture that allowed for serendipitous encounters and precipitated organic collaborations. He viewed the loss of their physical space at Rowell Rd as an emblematic one, alongside mainstays like The Substation.

For the Singaporean members (Urich, Yue Han and Melvin) who have remained active within the local arts and cultural scene, it seems there is a palpable, enduring sensitivity towards the ecosystem and their role in it. They acknowledge an all-too-familiar pattern: many of these initiatives, born from passion and necessity, have either become dormant, dissolved quietly or been absorbed into more institutionalised structures. Their reflections conveyed a concern for the health of the arts landscape and a personal ideological commitment to supporting independent, collaborative, generative spaces. In many ways, the impulse to create and sustain Hothouse can be read as part of this broader, emotionally and politically charged desire: to not only produce art, but to constantly cultivate spaces for experimentation, community and critical imagination within an increasingly professionalised and fragmented cultural terrain.

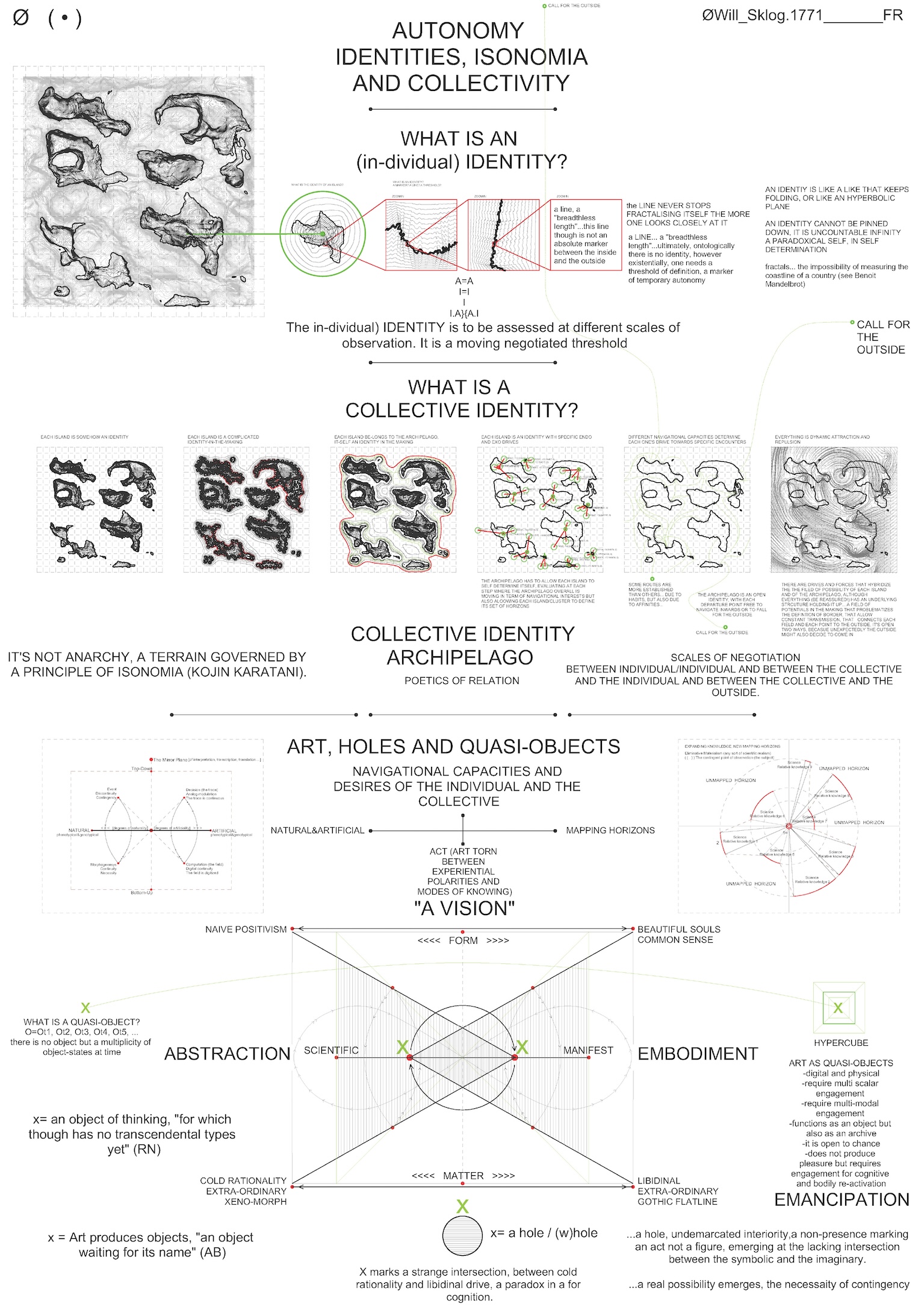

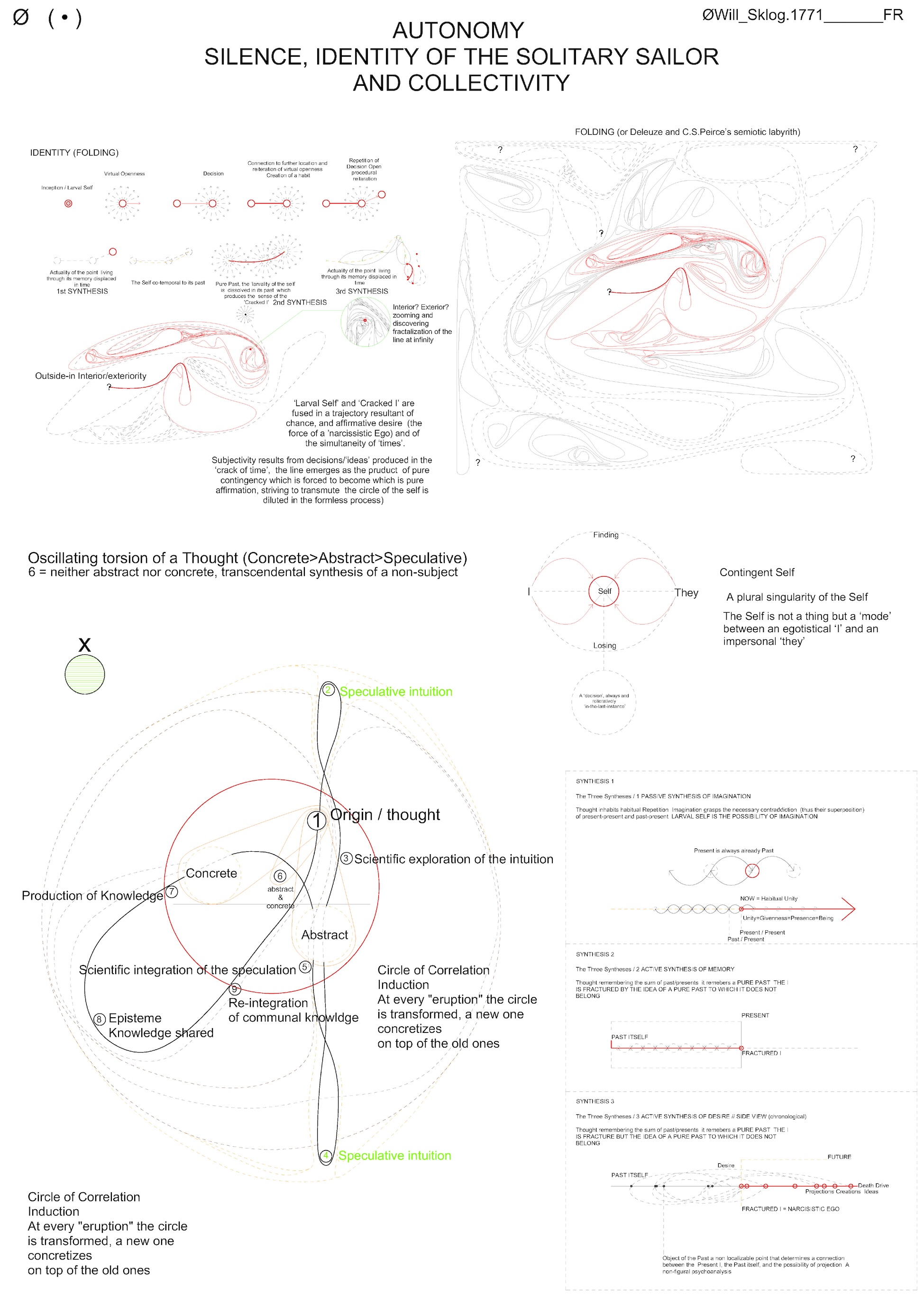

Embedded within these personal histories, we can start to surface and make sense of the differing expectations about what an art collective should serve. For Yue Han and Melvin, the spirit of altruistic, interventionist and experimental collectivism remains a central, animating force. As the collective evolved over time, especially with the integration of its newest members formAxioms, these foundational ideals sometimes find themselves in tension with newer pragmatics and shifting creative orientations.

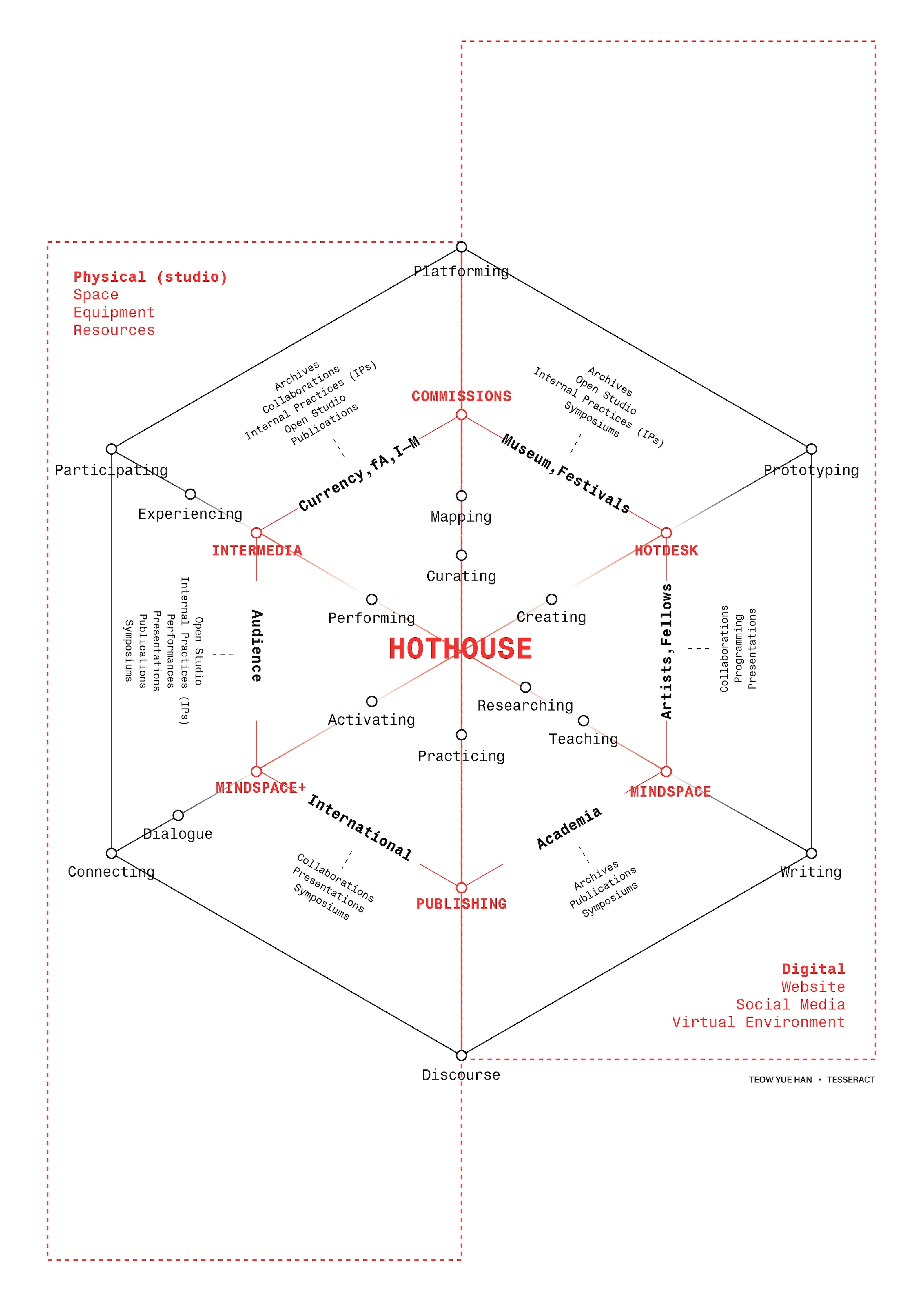

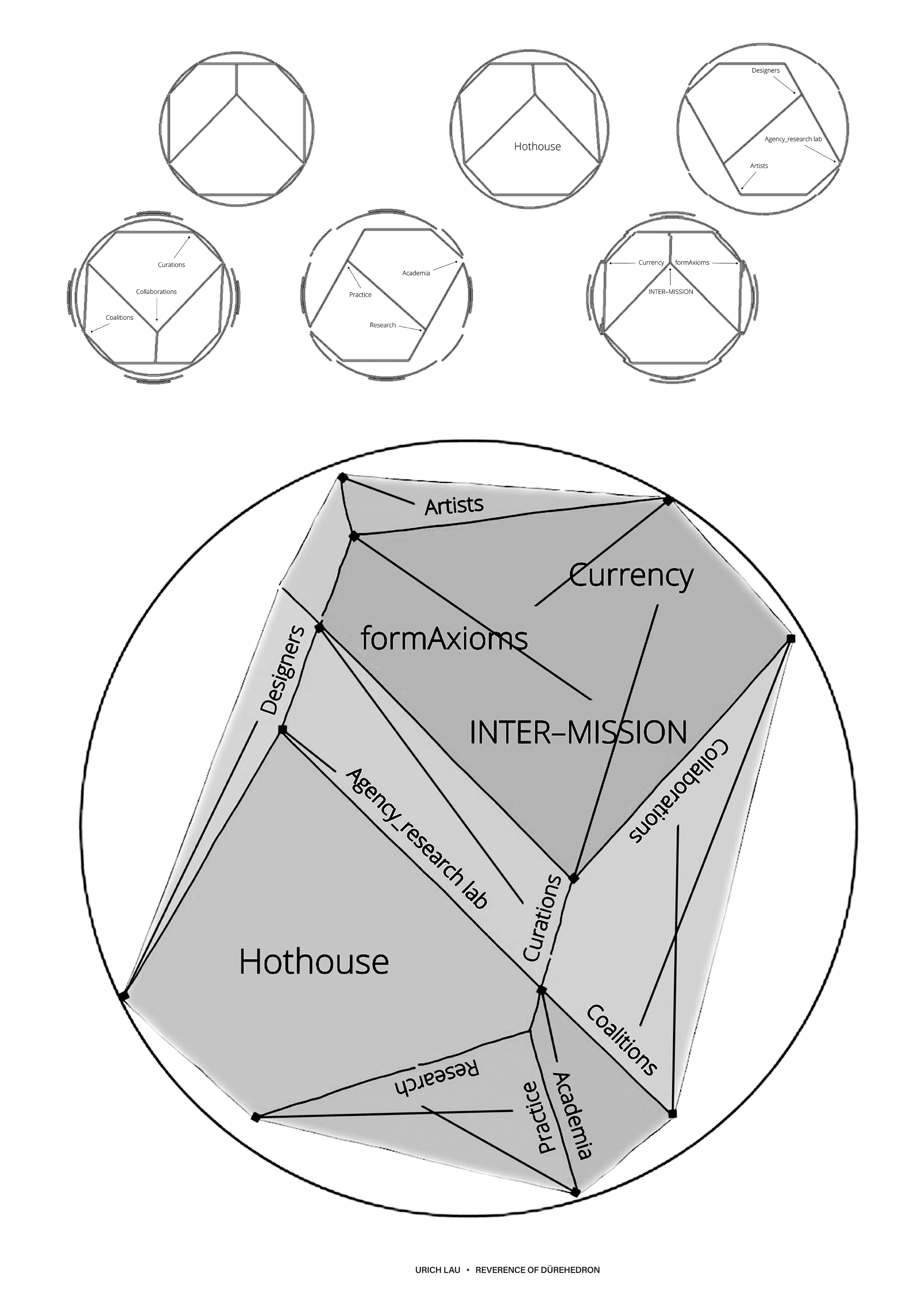

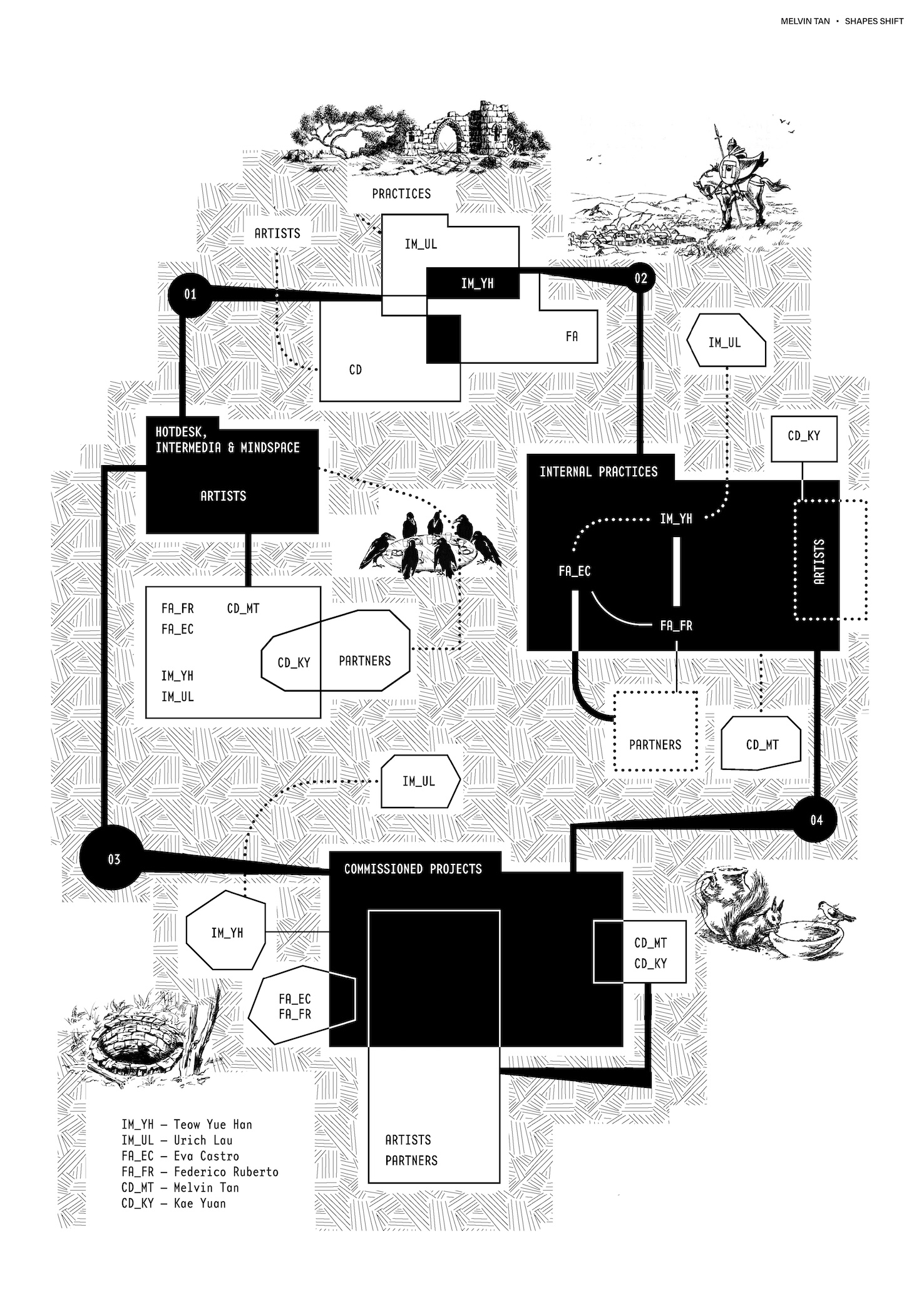

The formalisation of formAxioms as part of Hothouse, a process which took two years from 2020 to 2022, is consistently cited as a pivotal inflection point that shifted the collective’s trajectory. Prior to their joining, Hothouse was largely framed as a platform: a curatorial-facilitative space where INTER—MISSION and Currency primarily invited external collaborators to exhibit, present or produce. As Eva articulated, “Before formAxioms, it used to be more of a curatorial backslash facilitator kind of a team… they were like cultural agents.” Following major projects like Negentropic Fields, the collective shifted its focus towards more internal creative production. Its activities began including more original, generated works, experimenting with XR/VR mediums and building immersive art experiences. As Federico observed, Hothouse pivoted in their growing interest to “not only facilitate a platform for others but [also] engage in our own practices.”

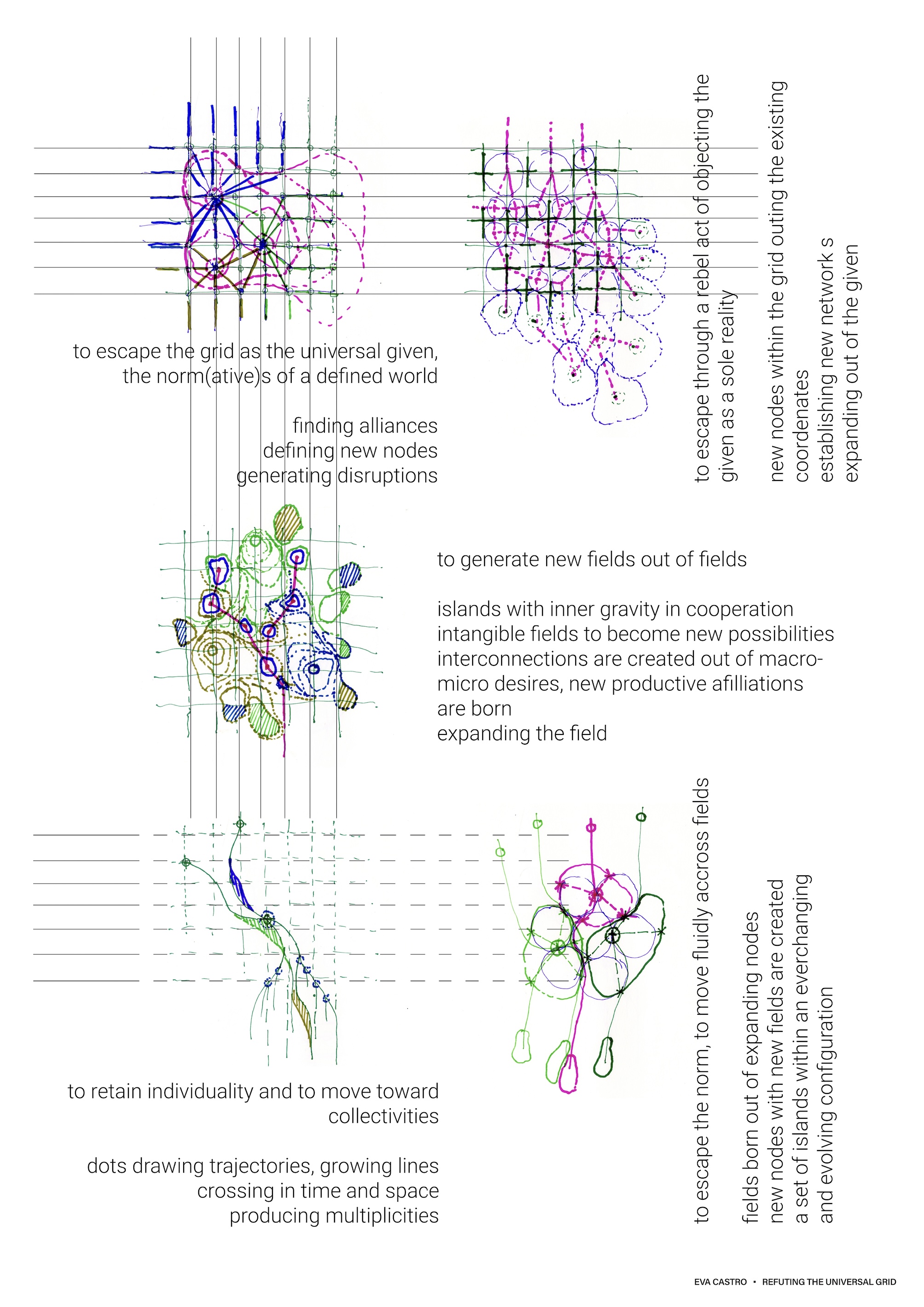

The entry of formAxioms also marked the evolution of broader paradigms and ideological currents. As practitioners originally based outside Singapore, Eva and Federico brought with them frames of references. Their investment in speculative technologies, immersive environments, and architectural world-building opened Hothouse to artistic languages less tethered to Singapore’s specific socio-political context, and more aligned with global currents in digital and expanded media arts. Eva herself acknowledged that from Negentropic Fields onwards, there was a growing aspiration to “connect almost anthropologically across various kinds of scales,” linking local and international practices.

In parallel, across the broader collective, there was also interest from Yue Han and Urich in particular to intentionally engage the international. Yue Han articulated a hope that Hothouse might one day become “one of the key spaces people think of when they think about the experimental scene in Singapore.” This is something which Urich echoed, expressing, “Whenever anyone from overseas or even locally want to look for artists or an art group that represents this amalgamation of collective, intermediate, mixed media practice… [I hope that] the first thing they see is Hothouse.”

For long-standing member Melvin, this evolution occasionally chafed against the original ideals of the open, altruistic, support of the local arts community approach that he and Yue Han championed in FOCA. Differences in expectations—around whether Hothouse's priority should be nurturing hyperlocal, relational communities or projecting outward—remained largely submerged, unspoken except during moments of heightened tension. It is only recently that these tensions have erupted into more open, direct confrontation between the members.

It is crucial to emphasise that these divergences are perceived bifurcations, not absolute divides. As Federico notes, the different modes of engagement reflect “different origin points, different ways of understanding forms of work, practice, boundaries... overlapping bridges.” Individuals move between registers, depending on context. Yet, because these differences are rarely explicitly surfaced, frictions accumulate silently. As Eva succinctly put it, “We put the clash under the table and we continue to work. But it reappears, oftentimes.”